Entries by Scott McPherson (423)

Federal grants begin to flow for prison and jail pandemic planning

The Department of Justice is not taking pandemic concerns lightly. In fact, the DoJ, through a grant from its Bureau of Justice Assistance, is bringing two major players together to begin pandemic planning in earnest.

The Department of Justice is not taking pandemic concerns lightly. In fact, the DoJ, through a grant from its Bureau of Justice Assistance, is bringing two major players together to begin pandemic planning in earnest.

Those players are the twin towers of corrections organizations: the American Probation and Parole Association (APPA) and the Association of State Correctional Administrators (ASCA). ASCA is the group that actually works with the head honchos of state corrections, so it is not merely a "trade" organization. It carries tremendous weight in the national -- and, by proxy, international -- corrections fields.

The ultimate deliverables expected by the Feds will include guidelines, strategies and identification of best practices.

We all know the concerns regarding how an influenza pandemic would impact public safety, but few understand the complicated world of corrections and how a pandemic would affect the entire foundation of prisons and jails.

First, the good news is that prisons are used to handling dangerous diseases. One only need Google the infection rates for HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis including MDR- and XDR-TB , MRSA and other staph, hepatitis and other dangerous infectious diseases among inmates to know that prison workers are exposed (forgive the pun) to dangerous and life-threatening diseases 24/7/365. They even routinely set up quarantine areas within prisons and shift entire prison populations during flu season, to lessen the effects of an epidemic.

That is where the good news ends, for then the crushing weight of reality comes down like a giant rock falling.

Second, the realization creeps in that in a pandemic, the safest inmates are also the most dangerous -- namely, those inmates placed into "close management" or solitary confinement conditions. Those inmates will already be isolated and therefore protected from the general population. Finally, if a pandemic reduces the availability of available uniformed correctional officers at a rate close to that of the working public -- a figure we all normally use, around 25 to 40 per cent -- then a facility with 1,200 inmates and 300 correctional officers (do NOT call them "guards") will be a damned difficult place to manage safely. In a situation where inmates see their comrades sickened and dying by the score, and authorities unable to isolate or treat them, panic and attempted escapes at an unprecedented rate may become a predictable occurrence. Today, wardens can order "lockdowns" and keep inmates in their cells for extended periods of time. Extended, but not indefinitely: Court actions will undoubtedly be pursued by inmates who want to get out and get some sun. During a pandemic, hopefully, governors will have considered this threat to public safety and included prison orders in their State of Emergency executive orders.

Additionally, county jails will fill with lawbreakers arrested for taking advantage of reductions in uniformed police and sheriff patrols. The counties will accelerate the movement of transferable inmates into the state corrections systems. This will have two impacts: It will overcrowd existing facilities, and it will potentially infect otherwise healthy prisons with sick county inmates. Without inciting a riot between county and state corrections administrators now, let me say the stories of counties dumping sick and/or -- in one fabled case, a dead inmate -- on State systems are legend.

Now throw into the mix the reality that many, if not most, state prison operations today have outsourced basic needs, especially food production. Outsourced meal providers (basically glorified cafeteria companies) are a constant and ongoing source of frustration with prison administrators, largely due to the companies' collective inability to satisfy basic nutritional needs on a daily basis. The complaints of prison officials regarding routine substitution of "mystery meat" for advertised beef sources was heard by yours truly multiple times during hallway conversations in my nearly six-year stint as CIO for the Florida Department of Corrections. That subject took on greater urgency when I was appointed to lead the Department's pandemic planning effort.

Simply put, many prison systems have lost the ability to self-sustain food production in a pandemic. Prison systems now "order out" for food -- and that means the national supply chain, and not the inmates' farming abilities, will be called upon to provide sustenance in a pandemic. If prison food vendors cannot provide nutritious food on a good day, based on past performance, why should we think they will be able to provide food at all during a moderate to severe pandemic? To me, this is the most worrisome element of all for prison pandemic planners: How to feed inmates during a pandemic.

Here is an article that appeared recently in Government Technology's Emergency Management magazine. The pandemic portion is toward the end of the story.

http://www.govtech.com/em/articles/118640?id=118640&story_pg=1

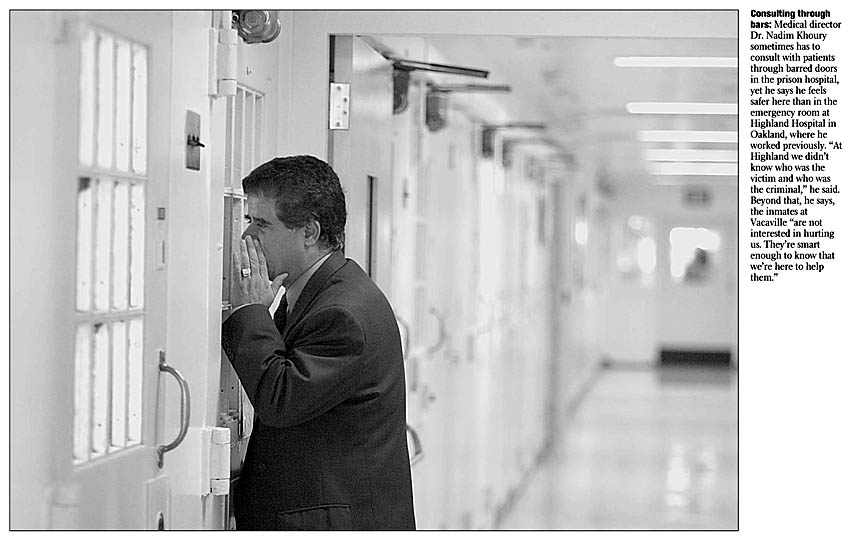

Photo credit sfgate.com. A physician "sees" inmates during a house call.

Singapore meeting might return us to those thrilling days of yesteryear.

Helen Branswell is regarded as a kind of Edward R. Murrow of infectious disease. She is what I would call a Tier One infectious disease journalist, a person who gets a kind of reception at a bird flu summit normally reserved for celebrities and world-famous politicians, or other medical correspondents such as Laurie Garrett and Gina Kolata.

Helen Branswell is regarded as a kind of Edward R. Murrow of infectious disease. She is what I would call a Tier One infectious disease journalist, a person who gets a kind of reception at a bird flu summit normally reserved for celebrities and world-famous politicians, or other medical correspondents such as Laurie Garrett and Gina Kolata.

She also convinces her bosses at the Canadian Press to fly her all over the world covering H5N1, so we benefit from the relationships she has cultivated among the bird flu intelligentsia over the years. Truly, the world is her "beat."

Currently, she is in Singapore, covering a not-too-well-publicized gathering of scientists and public health policy leaders, sponsored by the World Health Organization. Dr. David Heymann, the leader of the WHO infectious disease effort, is chairing the meeting.

Ms. Branswell reports in her by-lined article that the WHO's meeting is attended by representatives of 24 nations, including the Big Four for H5N1 infections in humans: China, Egypt, Indonesia and Thailand.

The issue is extremely dicey. This past January, as we all know, Indonesia's health minister (left) suddenly withheld vital H5N1 genetic samples, claiming intellectual property on the RNA. Since H5N1 was evolving/mutating in Indonesia, she claimed, the rights to all research should flow back to her nation. In fairness, it should be noted that this came - bada-BING! - immediately after an Australian vaccine maker produced a prepandemic vaccine made with WHO-certified Indonesian H5N1 antibodies, apparently without the host government's permission or consent.

The issue is extremely dicey. This past January, as we all know, Indonesia's health minister (left) suddenly withheld vital H5N1 genetic samples, claiming intellectual property on the RNA. Since H5N1 was evolving/mutating in Indonesia, she claimed, the rights to all research should flow back to her nation. In fairness, it should be noted that this came - bada-BING! - immediately after an Australian vaccine maker produced a prepandemic vaccine made with WHO-certified Indonesian H5N1 antibodies, apparently without the host government's permission or consent.

We should also know that the nations whispering into Indonesia's ear with counsel to upset the apple cart of H5N1 sample distribution are none other than -- drumroll and sabre-rattling, please -- Venezuela, Cuba, North Korea and Iran. So geopolitics and "nonaligned" (my foot) nations are being H5N1 provocateurs against what they see as the unwillingness of the West to share vaccine. Give us vaccine, Indonesia says, and we will give you samples. Of course, this is inside-out logic. You can't make a vaccine without the samples. So Indonesia also took the step of signing a contract with Baxter Pharmaceuticals of the USA. Baxter gets the samples; they get to produce the vaccine; and the Indonesian government gets its way and gets its vaccine.

But while we castigate the Indonesian government for its shortsighted decision, we should also recognize its concerns. The poor of the world don't get vaccine on a good day, for all the usual and apparent reasons. That is one reason why the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has suddenly and very publicly entered the H5N1 prepandemic vaccine fray, to its enduring credit.

But read Ms. Branswell's article closely. There is another, perhaps more insidious force at work here. Quoting from her story:

"That the ensuing vaccine would be beyond the reach of developing countries in a pandemic is the main source of the conflict, though complaints about the sharing of credit on scientific publications have also fuelled the fire."

Excuse me, but I thought we were all working on the same team here. It is one thing to have (varying degrees of) legitimate national concern about protecting its citizens. It is another to squabble about credit. We all know the axiom, "Publish or perish," meaning if you don't publish, you won't get coveted government and endowment/foundation grants. But considering the magnitude of the potential pandemic -- and the fact that governments are throwing research grant dollars around like beads at a Mardi Gras parade -- I think everyone can get a slice of the pie, right?

One of the best books I have read about infectious disease was Karl Greenfield's seminal work on SARS, China Syndrome. If you have not read that book yet, pick up a copy and read how back-door politics denied one researcher the chance to get his name in lights as the co-discoverer of the unique coronavirus that causes SARS. Apply the lessons learned to this situation. "Fight over academic credit stalls H5N1 breakthroughs", Branswell's headline might read, were it not for the fact she needs those sources to keep her abreast of what is actually going on "out there."

If the Singapore meeting falls apart without reaching consensus on how samples are to be distributed and analyzed, we could be thrown back to the world of the 1950s, when the Lone Ranger was on radio and that newfangled idiot box known as television was just coming out and the rich neighbors down the street were the only ones who could afford it. How so? We will revert back to Cold War-era sample sharing. Nations that choose not to share samples will hamper much-needed research on the virus. The world's researchers will be unable to collaborate, credit or none, on much-needed breakthroughs in the understanding of influenza itself (let alone The Next SARS, etc.).

If the Singapore meeting falls apart without reaching consensus on how samples are to be distributed and analyzed, we could be thrown back to the world of the 1950s, when the Lone Ranger was on radio and that newfangled idiot box known as television was just coming out and the rich neighbors down the street were the only ones who could afford it. How so? We will revert back to Cold War-era sample sharing. Nations that choose not to share samples will hamper much-needed research on the virus. The world's researchers will be unable to collaborate, credit or none, on much-needed breakthroughs in the understanding of influenza itself (let alone The Next SARS, etc.).

Let me remind the reader that the 1977 Russian Flu H1N1 rebirth was rumoured to have occurred because a Soviet flu lab experiment went awry. We would not have H1N1 around today, had it not been for that sudden re-emergence thirty years ago this month. Not too long ago, in a widely publicized "Doh!", a US flu lab mailed H2N2 (1957 pandemic) virus particles as part of its seasonal flu typing test kit. How will a lack of sharing impact the ability of the world to recognize a potential pandemic subtype, let alone prepare for it?

So prepare to return with us to those thrilling days of yesteryear, as we implore the Lone Ranger not to send Tonto to town! He might come back with more than a concussion and a sore jaw.

Researchers watch virus-sharing talks with trepidation, fearing science may suffer

| (World News) Tuesday, 31 July 2007, 08:43 PST | |

| by Helen Branswell |

“We're very conscious that this is a precedent-setting meeting, as are most of the delegations,” said Dr. David Heymann, head of communicable diseases for the World Health Organization, under whose auspices the five-day meeting is taking place.

That's because the talks could change the conditions under which biological materials are provided to the WHO for global surveillance of and research on influenza viruses.

Depending on what is decided, the consequences could ripple far beyond the science of flu, experts say, conceivably affecting, for example, the pharmaceutical industry's ability to make and update an eventual HIV vaccine or limiting how quickly the world could respond to the next SARS-like disease outbreak.

“I think there's a heavy responsibility on the meeting, and then on the intergovernmental meeting which will follow (in November), to make sure that above all, considerations are made for public health security,” Heymann admitted.

Four countries from each of the WHO's six regions are at the table, including Britain, Canada, the United States, Indonesia, Vietnam, Thailand and Egypt.

The need to update the rules for sharing flu viruses stems from the demand of several developing countries, led by Indonesia, for affordable access to pandemic vaccine when the next global flu outbreak occurs.

Indonesia, the country which has lost the most lives to the H5N1 virus, has for much of this year refused to provide patient samples (from which viruses can be retrieved) to the WHO laboratory network, using the viruses as leverage in this debate.

Labs at institutes such as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control or Britain's Health Protection Agency isolate and study these viruses at the behest of the WHO, looking for changes that might allow H5N1 to more easily infect people or to evade the drugs used to treat flu.

When asked to do so by the WHO, they also make seed strains from important new virus variants, providing them free of charge to pharmaceutical companies for use in the manufacture of vaccine.

That the ensuing vaccine would be beyond the reach of developing countries in a pandemic is the main source of the conflict, though complaints about the sharing of credit on scientific publications have also fuelled the fire.

Many observers fear measures devised to address these concerns could lead to restrictions on how viruses that flow into the WHO system can be used, even by scientists.

Most are not willing to speak on the record about what is at stake in these highly sensitive talks.

“People are concerned,” admitted Dr. Adolfo Garcia-Sastre, an influenza researcher at New York's Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

Some fear a system could evolve where WHO labs could only look for limited information from viruses fed into the network.

Some envisage a scenario where this information could only be fed back to the contributing country, which could choose whether or not it should be shared with the broader scientific community. If some countries agreed to amalgamate findings and others did not, that could lead to huge gaps in understanding about how a virus is evolving.

NOW maybe people will pay more attention to the flu epidemic Down Under!

Christina Aguilera cancels 2 shows due to flu

Christina Aguilera cancels 2 shows due to flu

NEW YORK - Christina Aguilera, who wraps up her world tour this week, has canceled two shows in Australia because she is ill with the flu.

Doctors confirmed the 26-year-old singer is suffering from a viral upper respiratory tract infection with a high fever and abnormal coughing, said concert promoter The Frontier Touring Company in a statement Monday released through Aguilera’s spokeswoman.

Aguilera was put on bed rest for several days, forcing her to miss two shows in Melbourne on Saturday and Monday.

“Unfortunately, I have fallen ill with a bad flu virus,” she said in a separate statement. “This is one of the best cities in the world to perform in and I am truly disappointed that I won’t be able to share my show with you all.”

Several people on her tour have also become ill in Australia, the promoter said.

Aguilera’s final two concerts were set for Thursday and Friday in Auckland, New Zealand.

New research defies conventional wisdom on influenza

When I put together a government group to tackle a tough job, part of my M.O. is to reach out to the nation's experts on (name of topic) and persuade them to give me free advice. So it is with pandemic influenza preparations. I reach out, and they reach back. I have found the nation's top "influenza rock stars" to be surprisingly approachable and willing to answer questions and give advice.

One of the world's foremost influenza researchers (who shall remain nameless) told me about a year ago, "I can’t promise to have the answers though, you will be surprised at how little we actually know." It was both refreshing and chilling to hear one of the world's most quoted and respected clinical researchers give that candid assessment.

It also points out how fragile our understanding of flu really is. And while we make certain assumptions about the virus, we also realize that when we get one answer, we wind up with a thousand new questions. Here are some of the previous postulates, along with the recent findings that dismiss them.

1. Tamiflu is only good for five years.

1. Tamiflu is only good for five years.

FALSE. Here's what the US government will do with its stockpile of Tamiflu, if the expiration date approaches and it has not been used (meaning no pandemic yet). The Department of Defense, along with the Food and Drug Administration, will check random boxes of Tamiflu from all of the secret Strategic National Stockpile locations. Yes, the stockpile is under armed US military guard. Samples of Tamiflu capsules will be tested to ensure the integrity of the capsules is OK. Then, the FDA will stamp a new expiration date on all boxes. However, the STATE-purchased portion of the Stockpile will not (at this time) be qualified for re-certification. But let's face it: If the boxes are co-located (which they are; State-purchased Tamiflu sits alongside Fed-bought Tamiflu until its distribution during the run-up to the pandemic), then basically State-purchased Tamiflu will keep as long as the US-bought antiviral.

By the way, store your own Tamiflu in a sock drawer. That is absolutely the best place to keep it, cool and dry. Dr. Mike Osterholm recently told a Council on Foreign Relations Webcast that he had no problems taking seven-year-old Tamiflu. So store it carefully and it will keep its potency.

2. The dreaded "reassortment" of influenzas -- meaning the sharing of genetic material between a human flu and an avian flu, leading to the creation of a new, pandemic strain -- can only occur in the winter months.

FALSE. The Institute of Research for Development in Montpellier, France, in conjunction with the Australian National University in Canberra, Australia, claim that reassortment can occur in any month, primarily in winter but not necessarily always. Researchers Andrew W. Park and Kathryn Glass reported their findings in the August issue of The Lancet Infectious Diseases, which I can never seem to find anywhere. Anyway, they report that between 2003 and 2005 the H5N1 virus was found in several new host species, including tigers, leopards, pigs, raptors, and domestic cats. But the greatest concerns are, first, the frequency with which the virus is found in domestic ducks, because the ducks have close contact with people, along with the isolation of the virus from pigs in China and Indonesia, because receptors in their respiratory tracts make coinfection with human and avian strains and thus generation of reassortant strains possible. Surveillance data from the Pacific basin from 1954 to 1988 show a marked variation in human influenza A activity, the authors say. They found that while consistent seasonality of viral activity between December and March occurs in Japan, patterns were not uniform across the rest of the region.

"Periods of moderate to high activity typically last longer in tropical and subtropical regions than in temperate regions, and they occur more frequently than once a year," Park and Glass write. "It is not prudent to assume there is a short period of risk of reassortment."

3. Influenza only travels an arm's length away when someone speaks, coughs, or sneezes.

FALSE. A May, 2007 study from Queensland University in Australia shows that droplet nuclei can travel well over a meter from the exhalant. The liquid component dries in the air, but the solid, dry residue can travel considerable distances, carried by a breeze or air conditioning system. According to Professor Lidia Morawska, this could lead to better-designed workspaces, improved ventilation systems and filtration technology. So maybe wearing masks should be mandatory in a pandemic (again) -- not to prevent catching flu, but rather to prevent spreading it.

4. Insects cannot spread flu.

FALSE. A North Carolina State University study supports initial Russian research that common houseflies can transmit influenza. Specifically, H5N1 has been found in the guts of houseflies and blowflies in poultry and wild bird outbreak areas, and previous studies during Pennsylvania's struggle with bird flu in the 1980s showed similar results. the virus may only live for 3 hours, but that is more than enough time to deposit the virus in a poultry shed or other environment.

5. Cluster cases of H5N1 are rare.

FALSE. A recent study conducted by the Ministry of Health in Jakarta, Indonesia -- supported by the US Navy's NAMRU-2 lab and the US Centers for Disease Control -- shows that 39% of all Indonesian H5N1 cases from July 2005 to June 2006 grew out of seven blood-related family clusters. That same study revealed that, while 76% of all H5N1 human cases appeared to be poultry-related, they could not identify the source of the remaining 24% of cases.

6. The "cytokine storm" that killed so many young adults in the 1918-19 pandemic and is killing so many young people today who catch H5N1, could be reversed and the patient would be saved.

6. The "cytokine storm" that killed so many young adults in the 1918-19 pandemic and is killing so many young people today who catch H5N1, could be reversed and the patient would be saved.

WE'LL GET BACK TO YA ON THAT ONE, BUT IT LOOKS FALSE. A brand-new study, conducted by the Pope of Influenza, Dr. Robert G. Webster of St. Jude's in Memphis, refutes the theory. Quoting the study: "These results demonstrate that inhibition of the cytokine response to infection with highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus is not sufficient to protect mammalian hosts from death." So we must continue to focus our research on the virus itself, rather than wasting time on shortcuts that lead to dead-ends.

Watching paint dry, OR Influenza is baseball

WARNING: I am going to mix metaphors like Emeril mixes cake batter in today's blog,

Events unfold so slowly on the influenza surveillance front, it is frequently akin to watching paint dry. Another human case in Indonesia, just this week. And a possible family cluster in the south central Nile delta. H5N1 strikes swiftly and hard against poultry in northeast India. These events, analyzed individually, are probably deemed irrelevant by most people, maybe even by some infectious disease experts. "Never mind that," they say. "Look at Dengue, stretching its tendrils across the world." And we certainly agree with that, but we also know that dengue, like malaria, can be controlled and beaten back through proper insect control, public health and sanitation measures. Dengue could arguably present a more immediate challenge to the United States than flu, because of ongoing outbreaks of dengue in neighboring Mexico and the potential likely ports of entry for dengue in America -- Houston, New Orleans, Tampa and Miami. But West Nile also exists in large numbers in the US, as does Lyme Disease, and you hear precious little about that duo.

Events unfold so slowly on the influenza surveillance front, it is frequently akin to watching paint dry. Another human case in Indonesia, just this week. And a possible family cluster in the south central Nile delta. H5N1 strikes swiftly and hard against poultry in northeast India. These events, analyzed individually, are probably deemed irrelevant by most people, maybe even by some infectious disease experts. "Never mind that," they say. "Look at Dengue, stretching its tendrils across the world." And we certainly agree with that, but we also know that dengue, like malaria, can be controlled and beaten back through proper insect control, public health and sanitation measures. Dengue could arguably present a more immediate challenge to the United States than flu, because of ongoing outbreaks of dengue in neighboring Mexico and the potential likely ports of entry for dengue in America -- Houston, New Orleans, Tampa and Miami. But West Nile also exists in large numbers in the US, as does Lyme Disease, and you hear precious little about that duo.

Without a doubt, pandemic fatigue is spreading like -- well, like a flu epidemic. A recent poll shows the lack of attention Americans are placing on the issue. People in the US -- people conditioned to hit the "reset" button on the XBox when the game doesn't go their way, or who want instant gratification on everything from their careers to the Iraq War -- just aren't focused on the likelihood of an influenza pandemic. When The Pandemic didn't happen in 2006, Americans lost interest and became somewhat jaded.

Complacency is the enemy of preparedness. It is a cancer that slowly takes over decision-making until the host is incapacitated. As I told the GAO when they were in town earlier this week: There are two camps in fluland. One camp says that each month that passes and does not bring us a pandemic pushes us ever further away from the next one. And then there are those who believe that each month that passes without a pandemic actually brings us closer to the next one, if for no other reason than we have pushed our luck too far.

Ask yourself: Which camp do you fall into?

But the facts are irrefutable that no disease on the Earth can compare to the infectious nature and mutation/evolution of influenza. Fortunately for us, we live in the 21st Century. Never before in the history of the planet have we had the surveillance network and arsenal of weapons to locate, identify and battle the virus. Never before have we had the technology to rapidly type, diagnose and treat the virus. And never before have we had the Internet to help us receive the information in close to real-time.

If the Internet existed in 1918, could the pandemic have been averted? Doubtful, but watching it unfold would have been possible. Had the Net existed in 1957, a pandemic probably could not have been averted, but its origins possibly delayed and tracked.

And that is what is going on today. Modern technology, science and medicine are allowing us to track the spread, evolution and species-jumping of avian influenza. Technology is helping authorities cull vast numbers of poultry. And one prominent researcher said (as I have mentioned in previous posts) that the odds are that Humankind has already killed a pandemic virus by culling poultry somewhere in the world. But we are no closer to stopping a pandemic than we were in 1918.

:"The Odds are?"  Odds, indeed. One must always play the odds. Life is played by the odds. Insurance companies play the percentages; their oddsmakers are called Actuaries. Risk assessment is playing the odds. It is baseball. Homeland Security is baseball. And influenza preparedness and response all over the world is baseball. You "play the percentages" and put in the lefty when the starter tires and the next batter is a behemoth who can't hit a curve ball thrown by a lefty. But the odds exist as a guideline, not as scripture. So the opposing manager lifts the batter and replaces him with a better-percentage hitter in the situation; the batter hits a seing-eye single sending home the winning run from third; and the game is over.

Odds, indeed. One must always play the odds. Life is played by the odds. Insurance companies play the percentages; their oddsmakers are called Actuaries. Risk assessment is playing the odds. It is baseball. Homeland Security is baseball. And influenza preparedness and response all over the world is baseball. You "play the percentages" and put in the lefty when the starter tires and the next batter is a behemoth who can't hit a curve ball thrown by a lefty. But the odds exist as a guideline, not as scripture. So the opposing manager lifts the batter and replaces him with a better-percentage hitter in the situation; the batter hits a seing-eye single sending home the winning run from third; and the game is over.

Sooner or later, and I am betting sooner, influenza will hit that seeing-eye single. The virus, standing on third, will use it as a launching pad and go home, to virtually every home on the planet. And we will see that all we did was buy time for the closer to warm up,