Federal grants begin to flow for prison and jail pandemic planning

The Department of Justice is not taking pandemic concerns lightly. In fact, the DoJ, through a grant from its Bureau of Justice Assistance, is bringing two major players together to begin pandemic planning in earnest.

The Department of Justice is not taking pandemic concerns lightly. In fact, the DoJ, through a grant from its Bureau of Justice Assistance, is bringing two major players together to begin pandemic planning in earnest.

Those players are the twin towers of corrections organizations: the American Probation and Parole Association (APPA) and the Association of State Correctional Administrators (ASCA). ASCA is the group that actually works with the head honchos of state corrections, so it is not merely a "trade" organization. It carries tremendous weight in the national -- and, by proxy, international -- corrections fields.

The ultimate deliverables expected by the Feds will include guidelines, strategies and identification of best practices.

We all know the concerns regarding how an influenza pandemic would impact public safety, but few understand the complicated world of corrections and how a pandemic would affect the entire foundation of prisons and jails.

First, the good news is that prisons are used to handling dangerous diseases. One only need Google the infection rates for HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis including MDR- and XDR-TB , MRSA and other staph, hepatitis and other dangerous infectious diseases among inmates to know that prison workers are exposed (forgive the pun) to dangerous and life-threatening diseases 24/7/365. They even routinely set up quarantine areas within prisons and shift entire prison populations during flu season, to lessen the effects of an epidemic.

That is where the good news ends, for then the crushing weight of reality comes down like a giant rock falling.

Second, the realization creeps in that in a pandemic, the safest inmates are also the most dangerous -- namely, those inmates placed into "close management" or solitary confinement conditions. Those inmates will already be isolated and therefore protected from the general population. Finally, if a pandemic reduces the availability of available uniformed correctional officers at a rate close to that of the working public -- a figure we all normally use, around 25 to 40 per cent -- then a facility with 1,200 inmates and 300 correctional officers (do NOT call them "guards") will be a damned difficult place to manage safely. In a situation where inmates see their comrades sickened and dying by the score, and authorities unable to isolate or treat them, panic and attempted escapes at an unprecedented rate may become a predictable occurrence. Today, wardens can order "lockdowns" and keep inmates in their cells for extended periods of time. Extended, but not indefinitely: Court actions will undoubtedly be pursued by inmates who want to get out and get some sun. During a pandemic, hopefully, governors will have considered this threat to public safety and included prison orders in their State of Emergency executive orders.

Additionally, county jails will fill with lawbreakers arrested for taking advantage of reductions in uniformed police and sheriff patrols. The counties will accelerate the movement of transferable inmates into the state corrections systems. This will have two impacts: It will overcrowd existing facilities, and it will potentially infect otherwise healthy prisons with sick county inmates. Without inciting a riot between county and state corrections administrators now, let me say the stories of counties dumping sick and/or -- in one fabled case, a dead inmate -- on State systems are legend.

Now throw into the mix the reality that many, if not most, state prison operations today have outsourced basic needs, especially food production. Outsourced meal providers (basically glorified cafeteria companies) are a constant and ongoing source of frustration with prison administrators, largely due to the companies' collective inability to satisfy basic nutritional needs on a daily basis. The complaints of prison officials regarding routine substitution of "mystery meat" for advertised beef sources was heard by yours truly multiple times during hallway conversations in my nearly six-year stint as CIO for the Florida Department of Corrections. That subject took on greater urgency when I was appointed to lead the Department's pandemic planning effort.

Simply put, many prison systems have lost the ability to self-sustain food production in a pandemic. Prison systems now "order out" for food -- and that means the national supply chain, and not the inmates' farming abilities, will be called upon to provide sustenance in a pandemic. If prison food vendors cannot provide nutritious food on a good day, based on past performance, why should we think they will be able to provide food at all during a moderate to severe pandemic? To me, this is the most worrisome element of all for prison pandemic planners: How to feed inmates during a pandemic.

Here is an article that appeared recently in Government Technology's Emergency Management magazine. The pandemic portion is toward the end of the story.

http://www.govtech.com/em/articles/118640?id=118640&story_pg=1

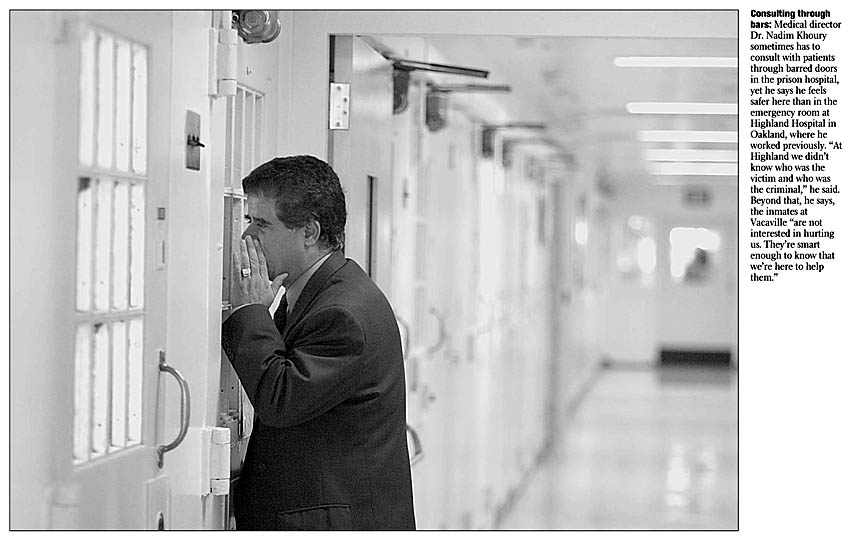

Photo credit sfgate.com. A physician "sees" inmates during a house call.

Reader Comments