Entries by Scott McPherson (423)

Jericho Season One DVD now available

After much anticipation, the inaugural season of the heralded post-nuke serial drama Jericho is available on region 1 (NTSC) DVD.

After much anticipation, the inaugural season of the heralded post-nuke serial drama Jericho is available on region 1 (NTSC) DVD.

What, you say? You never saw Jericho? Now is your chance to play catch-up -- and you have almost an entire year to do so! Just don't wait until then to buy the boxed set. You can read the backstory on the television show and how its faithful followers brought it back from the dead here: http://www.scottmcpherson.net/journal/2007/7/2/jericho-returns-to-cbs-july-6th.html

Jericho, Kansas is a fictional town near the Colorado border. Quickly it is caught in the crossfire of a terrorist act, as the terrorists detonate an uncertain number of nuclear bombs across America. When the Denver nuke explodes, it plunges Jericho into a post-apocalyptic world of uncertainty, rumors, and forced self-reliance. Where is the government? What is happening in the adjacent towns? Who bombed America? How will they feed all of the townspeople in the winter? How can they prevent lawlessness and chaos? Who can they trust? Who will step up and who will not?

Interspersed within this story are many intriguing subplots, some romantic, some involve deceit, infidelity, intrigue and possible treason, and some involving politics. In other words, something for the entire family! One continuing subplot involves the once-mayor, Johnston Greene, played in Emmy-caliber fashion by Gerald McRaney. Greene has been defeated for re-election, partly because he is so focused on keeping the town together, he did not bother to campaign. He also had a terrible bout with influenza during this critical post-nuke time, and almost died from the virus. Thought I would throw that one in there for all us flubies!

The populist themes of his victorious opponent quickly give way to the grim realization that Greene has what it takes to lead and the new incumbent does not. The new mayor then gives Greene authority to organize and train the Jericho townspeople to defend their territory against interlopers (rogue mercenary types with shadowy, Blackwater-esque tendencies) and, ultimately, against a rival town with a mad leader.

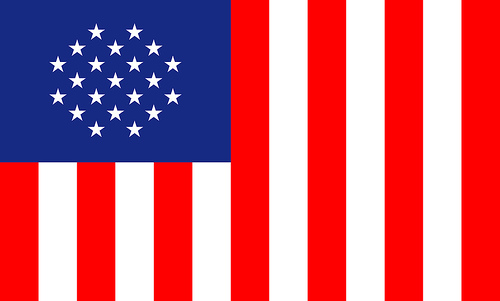

Which is where the first season ended: With chaos, the fog of war, and the hint of some sort of New American intervention to stop the conflict before it gets any bloodier (see flag at left).

Which is where the first season ended: With chaos, the fog of war, and the hint of some sort of New American intervention to stop the conflict before it gets any bloodier (see flag at left).

To tell you any more would spoil the surprise! And that surprise is how well the writers scripted, and well the actors played their roles, for this groundbreaking television show. Jericho is a serious television program for anyone who enjoys good apocalyptic fiction, science fiction, or survivalist fiction. Anyone in a post-9/11 world who speculates on what life would be like if "The Terrorists Win" should view this program. Anyone who ever read Pat Frank's classic novel "Alas, Babylon" will flock to this show like crazy. This show is also required viewing for anyone with a passion for emergency management and disaster preparedness. In fact, one of the featurettes in the boxed set is titled "What If?" The featurette speculates on America's current ability (or lack thereof) to withstand and survive man-made or natural catastrophes.

OK, here's the deal. After bringing the show back from the dead (again read my earlier blog on how an Internet campaign brought back the show), CBS ordered up seven new episodes for the Summer of 2008. CBS also threw down the gauntlet and said, "Show us the fan base is out there." And CBS will order up more episodes, if they see boxed set sales doing well. So this is your chance to view the phenomenon firsthand, and help bring back a show that we all can take notes from.

OK, here's the deal. After bringing the show back from the dead (again read my earlier blog on how an Internet campaign brought back the show), CBS ordered up seven new episodes for the Summer of 2008. CBS also threw down the gauntlet and said, "Show us the fan base is out there." And CBS will order up more episodes, if they see boxed set sales doing well. So this is your chance to view the phenomenon firsthand, and help bring back a show that we all can take notes from.

More from Zoe's diary

MSF, or what we better recognize as Doctors Without Borders, has posted the complete and ongoing diary/blog from Zoe Young, the healthcare worker at Ground Zero in DRC's Ebola outbreak. It can be found at: http://www.msf.ca/blogs/ZoeY.php and is required reading. Here's a passage:

MSF, or what we better recognize as Doctors Without Borders, has posted the complete and ongoing diary/blog from Zoe Young, the healthcare worker at Ground Zero in DRC's Ebola outbreak. It can be found at: http://www.msf.ca/blogs/ZoeY.php and is required reading. Here's a passage:

By the time I got back to the isolation unit, the third patient had died. He had been really very bad all day and his family had been outside crying and talking to him. His father had been in for a visit to say goodbye and they had cut two small pieces of string, one around his ankle and one around his wrist. Later in the morning they had asked Barbara to cut the last string which was round his tummy. It was awful to see: they were just waiting for him to die.

I went back to the cemetery and got two coffins into their graves before another torrential storm started with lightening that I could see streaking across the sky.

Excellent National Geographic article on emerging pathogens

It was with great sadness that I read an article off the Drudge report this morning. A young Arizona child died from a very rare (although getting less and less rare) lake-borne amoeba that attaches itself to the brain stem and literally eats away the tissue until the victim dies. The article states, in part:

It was with great sadness that I read an article off the Drudge report this morning. A young Arizona child died from a very rare (although getting less and less rare) lake-borne amoeba that attaches itself to the brain stem and literally eats away the tissue until the victim dies. The article states, in part:

According to the CDC, the amoeba called Naegleria fowleri (nuh-GLEER- ee-uh FOWL'-erh-eye) killed 23 people in the United States, from 1995 to 2004. This year health officials noticed a spike with six cases—three in Florida, two in Texas and one in Arizona. The CDC knows of only several hundred cases worldwide since its discovery in Australia in the 1960s.

Six cases, six deaths, 100% CFR. The article can be found at: http://www.breitbart.com/article.php?id=D8RUKBMG0&show_article=1 .

This brings me to the Article of the Month -- a National Geographic article on emerging pathogens that we all should read and absorb. Besides an excellent map showing the spread of H5N1 across the globe, it illustrates the huge problems confronting public health professionals as they try to discover, diagnose, and destroy these pathogens before they can make a permanent species jump to man.

I had never heard of Hendra virus, named for the location in Australia that spawned equine and human death in 1994. The article does a great job of introducing readers to monkeypox, Ebola, and other killers. Be sure to read the article, and better yet, go pick up a copy of this month's NG. The article can be found at:

http://magma.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/2007-10/infectious-animals/quammen-text.html .

Highly pathogenic H7N3 outbreak on Canadian poultry farm

If you are a "flubie," you are very aware of today's announced outbreak of H7N3 avian influenza on the Pedigree Poultry farm near Regina Beach, Saskatchewan. "Regina Beach" may conjure up scenes of frolic amidst the surf, but remember this town is on a river about 150 miles southeast of Saskatoon (Go Roughriders!). The town, interestingly enough, sits directly under the Central Flyway, one of the major (perhaps even THE major) migratory waterfowl flyways of North America. So take a huge waterfowl flyway, coupled with a river, and -- presto! - you have H7N3 emerging on a chicken ranch.

If you are a "flubie," you are very aware of today's announced outbreak of H7N3 avian influenza on the Pedigree Poultry farm near Regina Beach, Saskatchewan. "Regina Beach" may conjure up scenes of frolic amidst the surf, but remember this town is on a river about 150 miles southeast of Saskatoon (Go Roughriders!). The town, interestingly enough, sits directly under the Central Flyway, one of the major (perhaps even THE major) migratory waterfowl flyways of North America. So take a huge waterfowl flyway, coupled with a river, and -- presto! - you have H7N3 emerging on a chicken ranch.

What is also quite interesting about this outbreak is the use of the phrase "highly pathogenic" to describe the infection. We always shudder when we hear the words "high path," because that is an express ticket to a very, very potentially dangerous strain, even though the Canadian government is saying it poses "little risk" to humans. Here's why: As I mentioned several weeks ago in my blog regarding the presence of H7 avian flu in Egypt, the H7 strain loves people. It loves to jump to humans, and is a suspected agent for human-to-human transmission in multiple outbreaks worldwide. The last such outbreak just happened -- in Wales -- in May of this year. Over 250 British subjects were tested, and several wound up in hospital. If the H7N2 crossover had happened just a month or two sooner, during flu season, the consequences could have been disastrous.

The evidence is strong that in the Netherlands in 2003, for example, several dozen people who never handled poultry became sick with H7N7. A study confirming this H2H pattern is available for downloading at: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/eq/2005/04-05/pdf/eq_12_2005_264-268.pdf .

Quoting from the study:

In conclusion, our study suggests that human-to-human transmission of HPAI A/H7N7 can occur within household contacts in the absence of contact with infected poultry. Monitoring of clinical symptoms alone in household contacts of confirmed A/H7N7 cases underestimates the extent of human-to-human spread. In addition, our results suggest that cloth handkerchiefs, having indoor pet birds at home or having at least two toilets at home could be risk factors for household transmission A/H7N7 .

Taking all the results together, we recommend that during an outbreak of avian influenza: 1) Household members should be encouraged to use paper handkerchiefs instead of cloth handkerchiefs; 2) Household members of poultry workers exposed to A/H7N7 should be advised on enhanced general hygiene measures; 3) In the case that oseltamivir prophylaxis is offered to exposed poultry workers in future A/H7N7 epizootics, this should also be considered for household members of A/H7N7 cases; 4) Indoor pet birds of poultry workers should be screened and monitored during future outbreaks of avian influenza, in order to determine the role of indoor birds in household transmission of the virus; and 5) Further seroprevalence studies among contacts of asymptomatic persons with positive H7 serology should be conducted in order to assess the risk of person to person transmission, and consequently the potential for a new pandemic strain, in the absence of symptoms.

Don't forget that the H7N7 outbreak in the Netherlands also killed a veterinarian.

The Canadians have some prior experience in handling avian influenza cases in poultry. In fact, in what some would consider as foreshadowing, a report released at the very end of last year was highly critical of the Canadian government's handling of a 2004 outbreak of H7 in poultry. The CBC article can be found at: http://www.cbc.ca/health/story/2007/01/01/birdflu.html .

Study strongly advises goggles to protect against bird flu

Poultry workers did not comply with public health recommendations requiring them to wear protective goggles during British Columbia's avian flu outbreak in 2004, a new study suggests.

The H7N3 form of bird flu infected 1.3 million birds that year in the province and led to economic losses that were estimated at more than $300 million.

Dr. Danuta Skowronski of the BC Centre for Disease Control and her colleagues surveyed 167 people in the spring of 2004 to look at both cases of illness and compliance with recommended protective measures.

The only two human infections in the province occurred after direct contact with the eyes, which highlights the importance of wearing goggles, the team said. They found that the H7N3 strain of the disease caused mild eye infections.

"Recommended protective measures should be provided and readily accessible to any potentially exposed person during future outbreaks of avian influenza," the researchers concluded in Tuesday's issue of the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

"These precautions should be simple and feasible and should enable safe and unobstructed work; evaluation of compliance, effectiveness and impact should be undertaken."

When participants were asked about their biosafety concerns, eye protection was cited the most often. However, they said the goggles they used fit poorly over regular glasses, fogged up frequently or generally interfered with vision.

During the outbreak, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency provided protective gear to its workers but they were unable to give it to farmers, a difference that may be reflected in the results of the study, the researchers said.

Unlike a vaccine or antiviral medication, the protective gear has to be repeatedly donned and doffed, and compliance may be harder to recall, the study found.

The fear: A highly pathogenic H7N3 avian influenza mixes with seasonal flu in the lungs of a poultry worker, or a health care worker, a constable, or anyone else within miles of the outbreak. Remember that the epidemic of seasonal flu in the Southern Hemisphere that is going on as we speak is the worst in twenty years. And it is headed our way. If a nasty H3N2 or H1N1 variant reassorts with a high-path H7N3, we could wind up with a wholly new avian virus that loves a species jump to people. This is why it is so vitally important that the Saskatchewan authorities move decisively to contain this outbreak in poultry.

The story about the current Canadian outbreak is available at http://news.yahoo.com/s/afp/20070927/hl_afp/canadaanimalhealthbirdflu2 .

Death Takes a Vacation

OR: It's time to rediscover the theories of R. Edgar Hope-Simpson.

One of the most intriguing questions regarding seasonal influenza is just that: Why is influenza seasonal? Why is it that the virus only seems to move in the winter and spring seasons? Why doesn't it move year-round? It certainly isn't for a lack of hosts and victims.

This phenomenon is so prevalent that people have simply taken to shrug their shoulders and take the information as immutable fact and have ceased to question it.

All, save for some intrepid researchers at Penn State University (Go Nittany Lions!), plus some researchers at NIAID and NIH. http://pathogens.plosjournals.org/archive/1553-7374/3/9/pdf/10.1371_journal.ppat.0030131-L.pdf

They are (perhaps unknowingly, perhaps knowingly) continuing the work started three decades ago by the late R. Edgar Hope-Simpson, a British doctor. Dr. Hope-Simpson challenged the Conventional Wisdom of influenza researchers by claiming the existing theories about the spread of influenza were flawed in many places. He speculated (bear with me: I am only reading his book "The Transmission of Epidemic Influenza" just now, after eighteen months' worth of scouring the Internet for an affordable used copy) that influenza moves between humans all the time, but there is some significant event surrounding the autumnal equinox that seems to activate the virus and may also account for antigenic drift and shift.

They are (perhaps unknowingly, perhaps knowingly) continuing the work started three decades ago by the late R. Edgar Hope-Simpson, a British doctor. Dr. Hope-Simpson challenged the Conventional Wisdom of influenza researchers by claiming the existing theories about the spread of influenza were flawed in many places. He speculated (bear with me: I am only reading his book "The Transmission of Epidemic Influenza" just now, after eighteen months' worth of scouring the Internet for an affordable used copy) that influenza moves between humans all the time, but there is some significant event surrounding the autumnal equinox that seems to activate the virus and may also account for antigenic drift and shift.

Do not make the mistake of dismissing Dr. Hope-Simpson's work summarily. He was the first individual to postulate that shingles was caused by the chicken pox virus. Years later, someone else won a Nobel Prize off his research. A simple country doctor from Gloucestershire, he became one of Britain's most respected physician-researchers. I quote directly from his obituary in the prestigious British Medical Journal: http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/327/7423/1111?ck=nck

The bulk of his interest was in infectious diseases. He was self taught and without any formal epidemiological or research training, but he learnt fast. He established a small epidemiological research unit around his practice in 1946 and chaired a Medical Research Council committee.He started to write papers, particularly on chickenpox and herpes zoster, in the 1940s and 1950s, which were published in the Lancet and the BMJ, and he produced a series of publications of which many professors would be proud.

Chickenpox and shingles were known to be related, but how? Experts at the time were suggesting that two different viruses existed. Hope-Simpson increasingly believed there was only one, but how to prove it? In the end, he took his small team of research colleagues to the Island of Yell in the Shetlands in 1953 and literally followed up every known case in a much closed community. He was empowered by local islanders' memories for occurrences and dates. By 1962, new microbiological techniques enabled him to prove his point.

Only a great intellect could have conceived this possibility—that, remarkably, a virus could commonly lie dormant in the human body, for years, indeed decades, and then reappear in another form. Only an unusually determined researcher could have pursued the idea through fieldwork in the natural history tradition.

Hope-Simpson delivered his conclusion in the Albert Wander lecture of 1965, very properly and modestly describing it as his "hypothesis." His report became one of the most cited general practitioner publications. This was world class research in clinical medicine and Hope-Simpson made probably the most important clinical discovery in general practice in the 20th century.

Later the virus, now known as the varicella zoster virus (VZV), was identified and isolated, and the researcher responsible received a Nobel prize. Later still, a therapy for herpes zoster was developed and that research worker, too, received a Nobel prize.

Hope-Simpson never stopped thinking and reading, made many observations, and wrote a textbook on influenza. He retained his faculties until just before he died, saying how much he loved life, even in his final week.

What a selfless visionary! Self-taught, and free to make observations without the impediment of rigid scientific poo-pooing and inability to challenge the CW. And a man who would clearly be uncomfortable with the accolades afforded him in this blog.

Hope-Simpson's work has been latched onto by a posse that I call the "Vitamin D Gang," a group of doctors and researchers who believe strongly that Hope-Simpson's missing catalyst is none other than The Sun Vitamin. And there is some evidence to support that claim, but the jury is still out on the role Vitamin D plays in arresting influenza in the offseason.

Now back to the study, published in the Public Library of Science. The theory is that seasonal influenza heads for a vacation in the tropics, where it does all the things you would expect randy influenzas to do while on vacation: To frolic with other influenzas and engage in a shameless display of reassortment, over and over again. Then, when the vacation's up, these influenzas pack up and board the plane for each hemisphere until the Autumnal Equinox strikes and the viruses let go of their payloads.

Here are some key passages from the study:

Our large-scale phylogenetic analysis of A/H3N2 influenza virus populations from opposite geographic hemispheres provides evidence for regular bi-directional cross-hemisphere viral migration between seasons, even among localities as distantly separated as New York state and Australia and as relatively geographically isolated as New Zealand's South Island. Multiple genetic variants of influenza virus co-circulate each season, even in geographically remote areas, and many of these viral clades are more closely related to isolates from the opposite hemisphere than to isolates from either the previous or following season in the same location. Thus, viral populations do not appear to “over-summer” locally, where they would evolve in situ and give rise to the next season's epidemic. Rather, cycles of viral migration and recurrent introduction have clearly played a significant role in generating the genetic diversity that characterizes influenza A virus in both hemispheres. Importantly, given the sample composition of our sequence data set, the extent of cross-hemisphere migration observed here undoubtedly represents a conservative estimate. Hence, including data from more populated areas could only reveal more instances of cross-hemisphere migration.

In addition, our finding that the virus migrates globally between epidemics and is reintroduced is clearly compatible with tropical regions, including Southeast Asia, playing a key role in the genesis of new clades and the global spread of these novel influenza virus variants. Thus, while limitations in global genome sampling necessarily means that the current study is directed toward testing hypotheses of viral migration versus latency, equivalent data from tropical regions would undoubtedly enable us to conduct a more refined analysis of global migration patterns and their determinants. Specifically, if tropical regions serve as year-long influenza reservoirs, we would expect to observe phylogenies in which tropical isolates display the greatest genetic diversity and are positioned basal to viruses sampled from temperate regions. Consequently, complete genome sampling from tropical regions where influenza viruses circulate year-round, including a record of the precise date of collection, is of key importance for understanding the global epidemiology of the influenza virus.

Notably, the viral migration we observe does not appear to follow any clear pattern, but rather occurs in all directions, involves all genes, and involves clades of all sizes and geographic compositions. This argues against a role of immune selection in determining which viral clades are able to migrate among localities, although it does not preclude a role for natural selection as the sieve that determines which clades are able to survive in specific host populations. Similarly, the observation that migration patterns vary to some extent among the HA, NA, and concatenated non-surface glycoproteins must reflect the effect of widespread genomic reassortment [7,20]. Frequent reassortment complicates the analysis of migration patterns, as individual viruses can carry genomic segments with differing phylogenetic, and hence geographical, histories. Consequently, the analysis of migration patterns based on single gene segments may paint a misleading picture.

Similarly, the seasonal importation of multiple global isolates appears to be a greater contributor to the genetic diversity of the influenza virus population in New York state from 1997 to 2005 than local in situ evolution [7]. While our findings confirm that human population movements play a role in introducing new viral variants at the start of an epidemic, some aspect of climate is clearly of importance in triggering epidemics. Additional research is required to define how human susceptibility to infection and viral transmissibility fluctuate under varying climate conditions and why influenza virus is absent in summer in temperate climates but exists year-round in tropical zones.

The traditional focus on epidemic influenza may detract from the equally important epidemiological question of why influenza A virus does not circulate in humans for so many months of the year in temperate areas, especially given its apparent ability to infect humans in tropical areas year-round. Attempts to predict, model, or contain the spread of the influenza virus require a unified understanding of how the virus's spatial-temporal dynamics, antigenic evolution, and seasonal emergence interrelate [27]. (Bold type all mine).

OK, pretty fascinating stuff. Short form: Influenza takes a holiday in the tropics. The virus reassorts and then heads to the Four Corners, where some trigger changes either the virus, or changes us, and we become susceptible. But why people can get the flu in the tropics year-round, and others only get it in the fall and winter, is still unknown. The study, as one would imagine, calls for (among other things) a strenuous tropical surveillance effort.

Dr. Hope-Simpson died in November, 2003. Let's hope others keep his legacy and his spirit alive.