It's not always influenza that kills, part 4

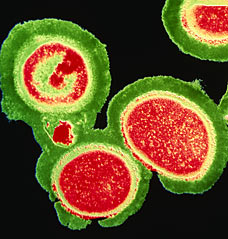

A bacteria almost as lethal and more difficult to kill than MRSA hitches a ride home on military personnel.

A bacteria almost as lethal and more difficult to kill than MRSA hitches a ride home on military personnel.

The London (UK) Daily Mail is reporting in today's editions about acinetobacter, possibly the nastiest bacteria on the planet. I'll let you read the article first, then scroll down.

Pandemic warning over the hospital superbug that resists safe antibiotics

Last updated at 00:00am on 1st April 2008

Doctors fear a pandemic of a lethal hospital superbug that is even more drug resistant than MRSA.

Staff battling outbreaks of acinetobacter are having to resort to antibiotics sidelined 20 years ago because of fears about their safety.

Even these do not always work, raising fears that the bacterium commonly found in soil and water could become uncontrollable.

Acinetobacter expert Professor Matthew Falagas said: "In some cases we have simply run out of treatments and we could be facing a pandemic with important public health implications."

More than 1,000 Britons catch acinetobacter every year. It is normally harmless, but can cause blood poisoning and life-threatening pneumonia in the vulnerable.

There are no official figures on fatalities but the superbug was linked to 39 deaths at St Mary's Hospital in Paddington, West London, three years ago. (bold mine)

It is thought many infections stem from soldiers returning from the Iraqi and Afghan deserts.

In 2003, 93 patients, including 91 civilians, were infected at Birmingham's Selly Oak Hospital, where servicemen were being treated on the same wards as other patients.

Thirty-five of those infected with acinetobacter died but the hospital was unable to establish if the bug was the main cause of death. (bold all mine)

Speaking at a Society for General Microbiology conference in Edinburgh, Professor Falagas warned that doctors were running out of options to treat acinetobacter. He said: "Doctors in many countries have gone back to using old antibiotics that were abandoned 20 years ago because their toxic side-effects were so frequent and so bad.

"But superbugs like acinetobacter have challenged doctors all over the world by now becoming resistant to these older and considered more dangerous medicines.

"Even colistin, an antibiotic discovered 60 years ago, has recently been used as a salvage remedy to treat patients with acinetobacter infections.

"And it was successful for a while but now it occasionally fails due to recent extensive use that has caused the bacteria to become resistant."

In contrast, MRSA, the bug more commonly associated with antibiotic resistance, is easier to treat.

Acinetobacter can survive on floors and furniture for almost three weeks. It tends to attack the seriously ill, such as cancer sufferers, car crash victims and burns patients.

The Health Protection Agency advises hospitals to isolate infected patients.

After the patient leaves, the ward should be thoroughly cleaned, with bedding disinfected or even thrown away to prevent further spread.

• Bacteria-killing viruses in medical products are being tested as a weapon against MRSA.

The "assassin" viruses, which are harmless to humans, breed inside MRSA bugs and kill them as they burst out.

Tests have been so successful that virus-packed stitches, dressings and detergents could be on the market in as little as a year.

Acinetobacter has been fingered as hitching a ride to the UK and the US via wounded soldiers and servicemen and women returning home from tours of duty in Iraq and Afghanistan. According to the website dedicated to awareness about the bug, http://www.acinetobacter.org/, this is becoming more and more common. This disease has also gotten the attention of such respected organizations as The American Legion. The following is from the March, 2008 issue of American Legion magazine:

Medical experts wary of dangerous germ now striking war‑wounded troops.

THE IRAQIBACTER

BY MARGARET DAVIDSON

Staff Sgt. Nathan Reed was escorting a CBS news team through Baghdad for a Memorial Day visit in 2006 when the car bomb went off. Reed survived, but his right leg was severely injured. He was rushed to military hospitals in Iraq and Germany, then to Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio.

The injured leg developed an infection from a bacterium called acinetobacter baumannii. Reed had to decide whether or not to have his leg amputated. He consulted his doctors. He weighed his options. Finally, after getting all the information he could, he went ahead with the surgery. "The Iraqibacter pretty much sealed the fate for my amputation," he says.

The bacterium nicknamed the Iraqibacter is an increasingly multi-drug-resistant supergerm that is plaguing wounded soldiers who served in Iraq. The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) has put it on a short list of six dangerous, top-priority, drug-resistant microbes. Doctors are running out of ammunition to fight it.

The Iraqibacter joins on that list a better-known and more common supergerm, methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Though less virulent than MRSA, acinetobacter baumannii is more drug-resistant. Not only does it possess a number of resistant genes itself, it also accepts resistant genes from other bacteria.

"I think it's unique," says Col. Glenn Wortmann, acting chief of infectious diseases at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, about the Iraqibacter's resistance, "and I think that's what has the IDSA so concerned."

Many infected soldiers respond to only a couple of different drugs. And Wortmann says he has encountered one or two isolated lab samples of the bacteria that were resistant to all antibiotics. "The issues with acinetobacter resistance are likely to continue to grow," predicts epidemiologist Arjun Srinivasan of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Acinetobacter (pronounced a-sin-EE-toe-back-ter) has quietly become a new cost of war in terms of the added time it takes infected soldiers to recover, the deaths of a few infected individuals, and the resources involved in treatment and prevention.

How widespread is the problem? Military and CDC representatives say they don't know because acinetobacter cases are not required to be reported. (bold mine)

Online bloggers accuse military officials of not being forthcoming about the extent of the problem. "They've done everything they can to play down the numbers," charges one of those bloggers, veteran activist Kirt Love, who is director of the Desert Storm Battle Registry.

One expert on the Iraqibacter, Maj. Clark K. Murray of Brooke Army Medical Center's Infectious Disease Service, disagrees. "We have published a large body of scientific work on the bacteria and have discussed with numerous media sources the impact of acinetobacter," he says.

Numbers are hard to pin down, but studies of U.S. military hospitals document a dramatic increase since the beginning of the war. For instance, at Brooke, 30 of the 151 injured soldiers from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars admitted to the hospital from March 1, 2003, to May 31, 2004, were infected with acinetobacter, up from only two infected soldiers seen there in the previous 14 months.

As case numbers surge, doctors face a declining number of treatment options because, Murray says, "the resistance of acinetobacter to antibiotics has increased over the war." Healthy individuals are at little risk, and young, physically fit soldiers are usually able to overcome the infection with the help of antimicrobial drugs that still work. But more vulnerable civilian patients in the same medical facilities have occasionally not been so lucky. Experts are divided as to what extent the Iraqibacter causes deaths. They say it is difficult to determine whether patients die as a result of the bacterial infection or from their underlying injuries or illnesses.

The bacteria can create a variety of problems, including pneumonia or meningitis and infections of the wounds, bloodstream, urinary tract or bones.

The source of the bacteria is a mystery. Types of acinetobacter bacteria occur naturally in soil and water worldwide.

However, much of the transmission of the bacteria to wounded soldiers seems to have occurred in military medical facilities. Military procedures now call for isolating and screening all incoming wounded from Iraq for acinetobacter. Strict rules of hygiene are observed to fight the bacteria, which can survive on surfaces for weeks. VA hospitals have similar requirements.

"This has the potential to become a serious problem in military and veterans hospitals, where soldiers returning from active duty worldwide are treated in the same environment as other patients," warns an article in the Journal of Clinical Microbiology.

However, the increasing drug resistance of a variety of bacteria is "not just a military problem," Wortmann says. "This is a problem that is

multinational."Margaret Davidson is a writer who specializes in medical issues.

http://www.legion.org/national/divisions/magazine/release?id=46

While the British have some pretty good stats regarding infection, I am at a loss to find comparable stats for the US. Perhaps someone can find numbers. Outside of the military, which always keeps meticulous details of diseases affecting its people, I cannot find any statistics for morbidity nor mortality. However, I do not think we are too far removed from the British example.

So why don't we demand better fact-gathering? As with adenovirus and MRSA, acinetobacter apparently does not warrant such time and effort. This should not be so: With so many people coming home from Iraq and Afghanistan with injuries and wounds, returning home to almost every town and city in America, and requiring continuing and ongoing medical care, why don't we keep better civilian statistics? We already know that hospitals are excellent breeding grounds for all sorts of communicable diseases. Soldiers, sailors, air force and Marine personnel are frequenting these medical facilities. And this is not a simple infection: This is major-league, killer bacteria we are talking about. This is stuff that makes MRSA look like a paper cut. Although MRSA is a badder bacteria, at least there are drugs that can wipe MRSA out. Today, at least. Acinetobacter, on the other hand, is less lethal, but is almost indestructible, so its bottom line is much worse than MRSA's. Plus, as you just read, it has a nasty habit of assimilating the nastiest habits of other bacterias.

There is an old saying I picked up at IBM: You Don't Know What You Don't Know. And we Don't Know the extent of penetration by acinetobacter into our communities, just like we Don't Know the penetration rate of adenovirus and MRSA. Just a few days ago, an outbreak of a "staph" infection occurred at a private clinic here in Tallahassee. The local health department was very quick to tell the community what it wasn't: It wasn't MRSA.

Great. So what is it? My guess is that in every community in America, similar stories and quick protestations of what it isn't are taking place. So let's find out what it is. And let's do a better job of tracking this most unwelcome present unwittingly brought home by our most welcome citizens, our returning military.

Reader Comments (2)

See also The Iraq Infections.

Thanks, Crof! Missed that one.