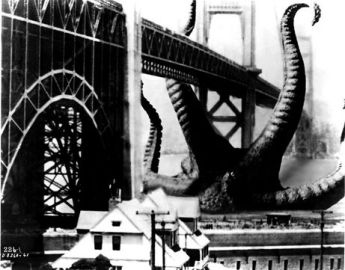

The ampersand that ate San Francisco; or, Why telecommuting will probably fail during a pandemic, Vol. 3

As veteran readers of this Blogsite know by now, I am decidedly pessimistic about the ability of the Internet to stay viable during a severe influenza pandemic. Not that I think the Internet will collapse, never to get off the canvas again. Far from it: Recall that it was the US military that built the ARPANET, as it was called back then, designed to withstand several simultaneous nuclear explosions via its "node" concept. ARPANET became the Internet (sorry, Al), and it still retains its ability to be resilient.

As veteran readers of this Blogsite know by now, I am decidedly pessimistic about the ability of the Internet to stay viable during a severe influenza pandemic. Not that I think the Internet will collapse, never to get off the canvas again. Far from it: Recall that it was the US military that built the ARPANET, as it was called back then, designed to withstand several simultaneous nuclear explosions via its "node" concept. ARPANET became the Internet (sorry, Al), and it still retains its ability to be resilient.

However, ARPANET did not have petabytes of pedophile photos, Internet porn, eBay auctions, pirate downloads of I Am Legend, illegal gambling, and YouTube videos to contend with like today's Internet does. So I think the Internet will be resilient, just slow as molasses and not dependable enough to base an economy around without making some pretty serious first-amendment content filtering decisions during a pandemic. If you search this Blogsite for "telecommuting," you will find my two previous entries on the topic.

I wanted to offer a history lesson to show how a simple mistake can bring down an entire region's telecommunications grid and impact hundreds of millions in commerce and threaten public safety. Then I will talk about a marvelous article the Dean of Flublogia, Crawford Kilian, found yesterday.

It was June 18, 1996. A network engineer with Netcom, a San Jose, California-based Internet Service Provider (ISP), was diligently working on configuring a Cisco router. Cisco is the company whose routers and switches and wireless access points basically run the Internet. In the course of configuring the aforementioned router, the engineer accidentally hit the ampersand (&) key on his computer -- and all Hell broke loose. You see, Back in the Day, that little ampersand was to Cisco routers what the end of the tape meant to Mr. Phelps. The command went downstream, as routers are designed to refresh commands down the line, and soon, the entire Netcom subscriber base of some 400,000 customers -- the entire San Francisco Bay area, basically -- was down for thirteen hours, all because the software that ran the routers became corrupted and incomprehensible.

That was twelve years ago, and many would argue there are multiple safeguards in place to prevent this from happening again. I would agree that much has been done to block such mistakes in the future, but also look at the adoption of the Web since 1996. If a similar mistake happened today, it would impact not just 400,000 people getting their email -- it would probably cost hundreds of millions -- if not billions -- of dollars in lost revenue, disrupted commerce, cancelled flights, and other problems. An old archive of this history lesson can be found at: http://www.merit.edu/mail.archives/nanog/1996-07/msg00074.html. The piece is written by none other than Bob Metcalfe himself. Remember Bob whenever you go to your keyboard and assess the Internet; for Bob invented the Ethernet protocol that allows your PC to actually communicate with the rest of the world.

Human error is not confined to telecommunications. As I mentioned in a blog a few weeks ago, here in sunny Florida, a fire at a Miami substation of Florida Power and Light wound up, via a major lapse in operator judgment, to bring down the Florida Grid for some 4 million customers. A well-placed government source recently told me the problem was exacerbated when a veteran technician overruled a well-worn protocol and decided not to reroute power in a proven way. The resulting cascading loss of power stranded hundreds in elevators and threatened public safety and transportation across most of Florida from Orlando south, on both coasts. FPL does not like errors in judgment, because the Japanese might come along and take back the Deming that FPL won a couple of decades ago.

So the Ampersand That Ate San Francisco can pop up at any time, anywhere, in varying disguises, because we humans are prone to making mistakes.

So the Ampersand That Ate San Francisco can pop up at any time, anywhere, in varying disguises, because we humans are prone to making mistakes.

Complicating things is this new malady, called Internet Addiction. Why this is a new malady is beyond me, for I have suffered from it for over fifteen years. As I promised a few paragraphs ago, Crawford Kilian, the Dean of Flublogia, has posted this article: Add Internet addiction to psychiatric disorders, says doctor. An excerpt:

Dr Jerald Block, the author of the editorial, points to both China and South Korea as nations that are more cognizant of the problem than the US. South Korea has seen a number of deaths at Internet cafes, and both China and South Korea consider internet addiction one of their more pressing public health concerns; an odd stance considering the much more palpable threats from emerging diseases such as avian flu and SARS. Nevertheless, there are recorded cases of people ignoring basic needs such as sleep or food in favor of lengthy sessions online, sometimes with fatal consequences.

I am aware of a few Asians who have died from lack of sleep/food/bathroom training when attempting some Internet gaming marathon, and that phenomenon is not limited to the Web, but covers all computer/console gaming in general. Since so many people do their gaming online, however, it merits serious consideration. My own stepson is constantly online, playing XBox Live with people from God knows where until the wee hours of the morning. At age 22, he is the perfect example of someone who would spend much of his time online during a pandemic. He already spends too much of his time online now!

Here's how it will work: During a pandemic, stuff will break. Stuff breaks now all the time, because all computer equipment is essentially mechanical in nature. Bearings in cooling fans in computers, servers and routers seize and the equipment overheats and fails. hard drives still fail. So does memory. During a pandemic, staff will be in short supply and stuff won't get fixed in the time frames that everyone enjoys today. Service Level Agreements, or SLAs as we call them in the biz, will be thrown out the window.

Next, the technician who comes to fix the stuff may or may not be a subject matter expert on the failed equipment. Two days before, that person might be the office receptionist, given coveralls and pressed into service if, for no other reason, to satisfy that four-hour response time promised on the damned SLA. That person may or may not be qualified to do what happens next: The initiation of a diagnostic routine to determine what broke and why. And The Ampersand lurks in the shadows like the monster in The Host, waiting for its next meal.

Next, the technician who comes to fix the stuff may or may not be a subject matter expert on the failed equipment. Two days before, that person might be the office receptionist, given coveralls and pressed into service if, for no other reason, to satisfy that four-hour response time promised on the damned SLA. That person may or may not be qualified to do what happens next: The initiation of a diagnostic routine to determine what broke and why. And The Ampersand lurks in the shadows like the monster in The Host, waiting for its next meal.

Now the final piece of the puzzle: The Just-In-Time Supply Chain. Computer and network equipment ain't made in Yonkers, folks. Almost every single piece comes from Asia. In a pandemic, Asia will be a little preoccupied, and despite the best intentions of the ChiComms and others to keep the containers sailing to America full of marketable goods, the pipeline will be squeezed to a trickle for weeks at a time. That translates into a longer time frame to fix stuff, because it will take longer to get replacement stuff in.

I have had a personal conversation with none other than Michael Dell on this topic. Dell's experience with SARS fuels its pandemic plans. Michael Dell knows that a pandemic is the mortal enemy of his company, and his people are investing a lot of capital -- intellectual and otherwise -- on this topic. Dell's entire corporate empire was built upon the rock of that JIT supply chain. Only now, the rock is moving and the temblor is a potential pandemic. I won't reveal Dell's plans other than to say he has one and he is banking a lot on it being successful.

So now you are home, trying to connect with the corporate mainframe while Junior is online, killing his buddies virtually. Your connection is slow anyway, because everyone else in the neighborhood is trying to do the same thing. Oh, I am sorry. You thought that cable connection was a Home Run (as we call it) right back to Al Gore's Man Room? Nope. Think party line and you get the concept that a big pipe gets cut up into little pieces and the more people on The Pipe, the slower the speed. And come to think of it, The Pipe may be a good metaphor for Internet addiction.

Suddenly, fifty miles away, The Ampersand lunges out and eats a technician's work. Your connection goes dead and Junior says, "Hey, what's that out the window?"

You respond under your breath, "That's daylight, you dingbat."

Speaking of The Host: If you watch the film, look carefully for the bird flu diagram which is prominently displayed during one sequence. You'll get a kick out of how they use it!

Reader Comments