Great Salt Lake die-off shows deadly power of North American migratory birds

An article that appeared a few weeks ago in the Salt Lake City, Utah Tribune underscores the need to remain vigilant regarding migratory wildfowl -- and the diseases they carry. It is also a shot across the bow of those who think migrating birds have gotten an unfair rap when it comes to carrying disease long distances. It does, however, validate the claim that wild birds can be as much a victim as a carrier, especially where this disease is concerned (read on).

An article that appeared a few weeks ago in the Salt Lake City, Utah Tribune underscores the need to remain vigilant regarding migratory wildfowl -- and the diseases they carry. It is also a shot across the bow of those who think migrating birds have gotten an unfair rap when it comes to carrying disease long distances. It does, however, validate the claim that wild birds can be as much a victim as a carrier, especially where this disease is concerned (read on).

Avian cholera killing water fowl at Great Salt Lake

Avian cholera is killing eared grebes, ducks and gulls on the Great Salt Lake in what is becoming an all-too-regular event on the important migratory bird flyway.

Prevailing northwesterly winds have blown about 1,500 bird carcasses into windrows along a half-mile stretch of the lake's southern shoreline near Saltair, Tom Aldrich, migratory game bird expert for the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, said Wednesday.

While the disease doesn't affect humans, people shouldn't pick up the birds or let their dogs chew on them, he said. Avian cholera has been confirmed in the eared grebes. Gull and duck carcasses have been sent to the U.S. Geological Survey National Wildlife Health Center in Madison, Wis., for analysis. "If I was a betting man, I would bet it was cholera," Aldrich said.

Introduced from domestic fowl during the 1940s, avian cholera has become the most common infectious disease among wild North American waterfowl but didn't appear in Utah until the late 1990s. In 2004, avian cholera killed about 30,000 eared grebes on the Great Salt Lake.

Avian cholera is a kind of blood poisoning that spreads quickly when the birds are overcrowded and food supplies are short. Scientists say death occurs so quickly that birds can fall from the sky or die while eating without showing signs of sickness.

http://www.sltrib.com/outdoors/ci_7871181

The disease is not limited to Utah birds, however. A more recent article in the Stockton, California Record also laments the appearance of avian cholera.

Birds diagnosed with avian cholera

http://www.recordnet.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20080112/A_NEWS/80111014

And still another article, this time from the Eureka, California Times-Standard:

Waterfowl hit hard by cholera

Thousands of waterfowl have succumbed to disease over the past month in one of the worst outbreaks of avian cholera on the North Coast in more than 60 years.

The California Department of Fish and Game alone has collected at least 3,500 dead birds, most of them American coots, since a rancher in Del Norte County first reported a die-off on Dec. 15. That means that many more birds died from the fatal bacterial infection.

”You could assume the numbers that we're finding are the bare minimum,” said Jeff Dayton, a biologist with Fish and Game.

Avian cholera was first documented on the North Coast in 1945. Since then, outbreaks crop up every three or four years on average. Generally, biologists pick up about 1,000 birds during an episode of avian cholera, although some 3,700 were counted during a major outbreak in 1977, said Richard Botzler, a wildlife researcher at Humboldt State University. In December 1998 and January 1999, biologists collected 5,100 birds.

Several hundred more dead birds have been picked up by biologists in Stanislaus, San Joaquin, Glenn, Butte and Sutter counties. Fish and Game sent samples to California Animal Health and Food Safety labs to confirm the presence of the disease. The samples were also tested for avian influenza -- or bird flu -- but came up negative.

In Asia, avian influenza is often detected during bird die-offs, said Fish and Game waterfowl biologist Dan Yparriguerre. Because of the concern about the possibility for bird flu to spread in the United States -- and the potential for a strain of bird flu that could affect humans -- biologist have stepped up their sampling efforts, he said.

Avian cholera is not transmissible to humans. It tends to occur when birds get stressed, and possibly when they are huddled together during chilly weather.

”As soon as we get our cold snaps you can just about count on it,” Yparriguerre said.

Coots are especially vulnerable, since they crowd together in large numbers, but all birds are potentially affected. In the San Joaquin Valley recently, about 200 Aleutian cackling geese were collected after dying of cholera.

There is little to do to prevent an outbreak, Dayton said, but Fish and Game is encouraging landowners to keep an eye out for dead birds and to collect them and bury or burn them if they find any.

John Driscoll can be reached at 441-0504 or jdriscoll@times-standard.com.

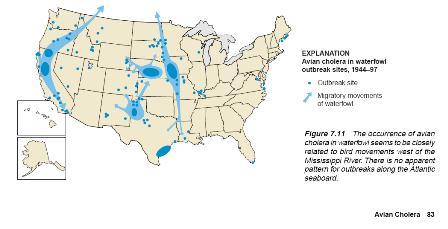

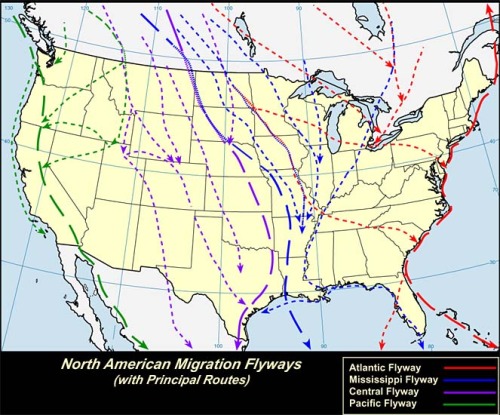

Avian cholera, or Pasturella Multiocida, is a bacteria. According to the Field Manual of Wildlife Diseases - Birds, published and used by the US Geological Survey, avian cholera has a fairly predictable pattern. Look at the chart from Chapter Seven - Avian Cholera, at the top of this blog. Now compare the appearance of avian cholera with the migratory wildfowl map here.

Avian cholera, or Pasturella Multiocida, is a bacteria. According to the Field Manual of Wildlife Diseases - Birds, published and used by the US Geological Survey, avian cholera has a fairly predictable pattern. Look at the chart from Chapter Seven - Avian Cholera, at the top of this blog. Now compare the appearance of avian cholera with the migratory wildfowl map here.

The lessons of avian cholera can be easily carried over to avian flu. Imagine if domestic fowl were somehow infected with H5N1. The disease is then carried over to wild birds, instead of vice versa. The migratory birds then move, and transmit the virus to other domestic fowl. This pattern repeats itself over and over again until we have our own "Clade" of avian H5N1.

The chapter is: http://www.nwhc.usgs.gov/publications/field_manual/chapter_7.pdf

Now, I want to awaken those who think that there is no such thing as backyard poultry in America. HAHAHAHAHHAAAAAAAAAA! Are you WRONG! First, I will tell you about one of my nephews, who lives on an island off the coast of Washington State. He is a farmer. He has also raised a rooster to be his pet. He (the rooster) comes into the home during the day and returns to his coop in the evening. Kind of like a Peabody Hotel without the $175 a night rooms and chicken instead of duck.

Anyway, I have told his father that his son is MAD. I have pointed out the location of the island -- in the thickest part of the Pacific Flyway. Oh well, all you can do is all you can do. But how about this AP article from December, 2007, that was picked up by MSNBC, ABC News and other sources:

Pet chickens may be plucked from owners

CHICAGO - Chicago's City Council is poised to send a message to residents: We don't want your clucking chickens.

Coming up for a vote Wednesday is a proposal to ban chickens, a former barnyard denizen that is pecking its way into cities across the country as part of a growing organic food trend among young professionals and other urban dwellers.

Chicken lovers say the birds make great pets, do not take up much backyard space and provide tasty, nutritious eggs.

Cities including Madison, Wisconsin, and Kent, Washington, have passed ordinances allowing people to keep chickens. In Ann Arbor, Michigan, a councilman says he plans to introduce a resolution to allow hens to be kept for eggs, and the Board of Zoning Appeals in the upscale Indianapolis suburb of Carmel recently approved an exception to city rules to allow a family to keep three hens in their backyard.

But the Chicago alderman who proposed a Chicago ban say chicken lovers forget that the birds attract rodents.

"This past summer I started hearing that residents were letting chickens out of their yard and they were leaving poop and mice were feeding off of it," said Alderman Lona Lane. "Then we started getting rodent-control problems and, sure enough, it was the chickens."

There are also concerns about parasites the birds might carry, and the possibility that they could transmit bird flu if it makes its way to the U.S., said Dr. Marek Digas, the supervising veterinarian at the city's Commission on Animal Care and Control.

"It is something we should consider," he said.

Rooster racket

Many neighbors of chicken-keepers are not happy, either. This year, the city received more than 700 complaints about chickens — though mostly about the racket from roosters.

"We don't encourage people to keep roosters because of the noise," said Johannes Paul, one of the founders of Omlet, a British company that sells a dome-shaped chicken house called the eglu in the U.S for $495.

"The chickens will produce eggs more than happily without a rooster around," Paul said.

Chicagoan Kim Jackson said her two chickens, Papoo and Chalmers, do a little quiet talking but that's it.

She says they do not smell, largely because she and her husband regularly clean up after them. But even if they did not, "it's not nearly as bad as a dog as far as how far-reaching the smell will get," she said.

Fresher eggs

Although there are no firm statistics on the number of city chickens, they are becoming so popular that Backyard Poultry magazine was relaunched a couple of years ago after halting publication in the 1980s. And Paul said U.S. sales of his company's designer chicken coops have doubled every year since they were introduced here in 2005.

Those who have eaten eggs from their own chickens say they are far fresher and tastier than store-bought eggs.

"And they're so productive for the garden," said Owen Taylor, training and livestock coordinator of Just Food, a New York-based nonprofit group. "They aerate the soil, eat bugs and they look like little tractors, tilling the soil."

Taylor said he was surprised that Chicago — a city that banned foie gras in restaurants over concerns about cruelty to geese and embraced rooftop gardening — is not more welcoming of chickens.

"The mayor has bees on the roof of City Hall so I was thinking Chicago was ahead of its time in terms of livestock regulations," said Taylor.

Some say the experience of chicken-keepers in other cities proves Chicago's proposed ordinance is unnecessary.

"You hear the same argument (that) they're loud, they smell ... that there would be wild chickens running amok in Seattle, but that hasn't been the case,' said Angelina Shell, of Seattle Tilth, a nonprofit organic gardening and urban ecology group.

What may doom them in Chicago, say chicken supporters, is that for all the talk about noise, smell and disease, chickens simply do not look like they belong in today's modern city.

"It's a gentrification issue," said Erika Allen of Growing Power, a nonprofit group that promotes urban gardening around the country. "People move in and they don't want chickens next to their house so they go and complain."

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/22215439/ (bold all mine)

Chicagoans, obviously tired of seeing their beloved Cubs choke year in and year out, have decided to adopt chickens and put them in their backyards. So what makes Chicago, or Ann Arbor, or Madison, any different than Kolkata, Tangerang or rural Britain? Only the absence of high-path H5N1 -- for now.

References (1)

-

Response: university

Response: university

Reader Comments (2)

Here are some pictures of the die-off at Great Salt Lake this year:

http://greatsaltlakephotos.com

Stunning photography, and an equally stunning -- and sad -- view of the die-off. Thank you for sharing your incredible photography with us!

Scott