Spores from Space?

Jim Oberg has written a dandy little piece of cosmic speculation. Jim, or James Oberg as you may know him, is one of America's best space writers, and is also an expert at Russian space history. His seminal work Red Star in Orbit is one of my all-time favorite books, and has nifty pictures such as cosmonaut group photos -- and the same photos with certain cosmonauts airbrushed out, which helped the CIA determine which Soviets went up but never came back.

Jim Oberg has written a dandy little piece of cosmic speculation. Jim, or James Oberg as you may know him, is one of America's best space writers, and is also an expert at Russian space history. His seminal work Red Star in Orbit is one of my all-time favorite books, and has nifty pictures such as cosmonaut group photos -- and the same photos with certain cosmonauts airbrushed out, which helped the CIA determine which Soviets went up but never came back.

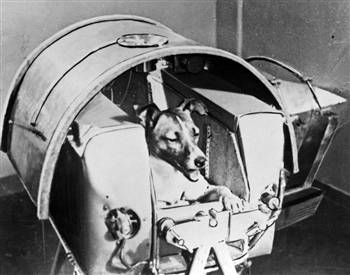

Anyway, Oberg recognizes that this is the 50th anniversary of not only Sputnik, but "Muttnik," when spacedog Laika was blasted into orbit. The article, titled "How a dog blazed the trail for life in space -- Russia’s Laika and microbial hitchhikers were launched 50 years ago" can be read in its entirety at: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/21596557/

Oberg writes specifically about the microbes that Laika carried with her into space -- and postulates that some of those microbes are still floating in space, or may have settled on the moon. Read on:

Even during that first flight, Laika did not ride alone. Like all advanced organisms on Earth, the dog carried an array of microorganisms in every nook and cranny of her body. Laika herself died of overheating just a few hours after launch, due to a thermal control system failure — a fact concealed by the Russians for decades. But that was hardly the end of the voyage.

Even during that first flight, Laika did not ride alone. Like all advanced organisms on Earth, the dog carried an array of microorganisms in every nook and cranny of her body. Laika herself died of overheating just a few hours after launch, due to a thermal control system failure — a fact concealed by the Russians for decades. But that was hardly the end of the voyage.

The other living organisms in Sputnik 2 would have continued to thrive for the nearly six months the satellite remained in orbit, living off the biological materials and water provided by Laika’s body. Temperatures inside the inert vehicle were well within the range in which Earth life can function, and the pressurized cabin would have remained intact.

Everything was destroyed — and likely sterilized — when the satellite slipped into the upper atmosphere on April 14, 1958. The forms that the "Laika biosphere" took can only be speculated about. But some microbes almost certainly survived until the very end.

Humans may be contaminating the solar system by the most innocent of methods. Here's a report about a technician with a cold, who might have further contaminated the moon:

A decade later, an even bolder small step for earth germs may have occurred when a worker at a spacecraft workshop in California sneezed on a television camera he was assembling. Installed in the Surveyor 3 robot moon lander, the device landed on the moon in April 1967. Apollo 12 astronauts retrieved samples of the lander in November 1969, and when several spots inside the camera were tested in a laboratory for microorganisms, one sample turned out to provide viable human-borne germs.

That idea has a broader but still widely unrecognized implication: Such conditions — exposure to terrestrial contamination during manufacture, followed by protection in a survivable environment after launch — also could apply to dozens of other space vehicles that have been launched to the moon, Mars and Venus. This is particularly true for Russian space probes, where deliberately pressurized canisters hold the electronics.

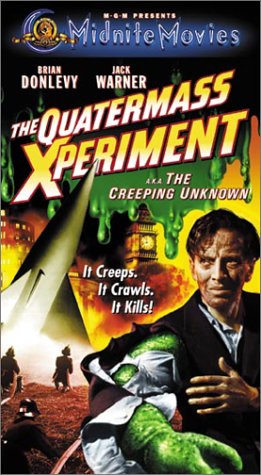

The thought of our own germs coming back to haunt us in strange and alien-mutated ways has always been a staple of science fiction. My personal favorite in the genre is The Quatermass Experiment (aka The Creeping Unknown with Brian Donlevy, one of my favorite movies of all time). However, in the vacuum of space, with no gravity and with an interesting playpen of humans living in a canister together, the possibilities for a mutant bacteria or virus are legion. Oberg continues:

The thought of our own germs coming back to haunt us in strange and alien-mutated ways has always been a staple of science fiction. My personal favorite in the genre is The Quatermass Experiment (aka The Creeping Unknown with Brian Donlevy, one of my favorite movies of all time). However, in the vacuum of space, with no gravity and with an interesting playpen of humans living in a canister together, the possibilities for a mutant bacteria or virus are legion. Oberg continues:

It’s impossible to know how long microbes or spores could survive in dormant state. Certainly, barring an accidental splash or two of borscht, they would have had no nourishment for growth. Maybe someday it will be possible to retrieve one of those early interplanetary probes and take a look — if the descendants of its original inhabitants permit it!

Closer to Earth but still in space, the lustiness of microbial growth is strikingly illustrated by experience on long-term space stations, such as Skylab (where bacteria probably thrived for years on garbage and human waste in the craft's trash module) and on the Russian Mir station, where fungi colonies actually grew on portholes (feeding on human skin peelings) and were so thick they obscured the view. (bold mine)

The fungi on Mir also excreted highly corrosive waste products that actually etched into the porthole glass and its titanium frame. Russian scientists found that the fungi and other microorganisms mutated wildly in the higher radiation levels of space. (ditto)

Researchers already have found that when salmonella bacteria were carried into orbit, they morphed into a new strain that was even deadlier when it was brought back to Earth. In the far future, the most dangerous space aliens might turn out not to be aliens at all — but rather the creatures we've been bringing with us to the final frontier, starting 50 years ago with one dog and several million microbial hitchhikers. (bold again mine)

The quarantine the Apollo 11 astronauts endured (and their fellow sojourners) was a dang good idea. No telling what alien life forms might have hitchhiked along with them! This does, I think, bring up an excellent point about the possibility that future microbial life on distant planets and planetoids might be terrestrial in origin, after all.

Reader Comments (2)

While I won't claim that they're 100.000% effective, NASA does take pains to prevent microbial contamination of space. Planetary probes have been sterilized with radioactive gas, I believe, just prior to launch, but current practice is "dry heat". The topic is known as "planetary protection", if you want to Google it.

do you suggest, earth-microbes might not only

survive, but even mutate -and thus replicate-

in space ? Without host-cells ?