Entries by Scott McPherson (423)

WHO belabors the obvious on move to Phase 6 for swine H1 pandemic

A blind man could see it in a minute: the World Health Organization, after a series of good moves and sound decisions, has blown the non-call on its reluctance to move the world to Phase 6 swine flu H1 status.

Why not Phase Six? A technicality: According to Helen Branswell of the Canadian press, Chile is in the WHO's North American reporting region. Now, that is like saying Japan is in the European region. But apparently the WHO is not too keen on Southern Hempsihere geography, else they would have a separate reporting schema for South America. factor in Chile, and presto! You have a Phase Six tripwire. According to Branswell, however, if Britain or Australia show community spread (and they will, no doubt about that), the WHO has no choice.

Therefore, functionall there can be no doubt -- no doubt at all -- that the world is in the beginning (yes, the beginning) of a real, honest-to-God influenza pandemic. Yet for the WHO and for so many nations whose preparations wholly centered around a killer avian flu with a severe death rate, they failed to take into account one small detail.

What if the pandemic isn't all that lethal?

First answer: Excellent! We'll take a 1957 or 1968-type pandemic over 1918. Or 1830. Or even 1946's near-miss.

Second question: Why couldn't these best and brightest conjure up a scenario that would involve just what we are facing right now?

Second answer: Because public health professionals are not distinguishing themselves well as emergency managers or homeland security planners. It is amazing to see the number of nations who never planned for a minor pandemic, and now are crying to the WHO to loosen the protocols. Heck, even the WHO itself has flirted with a rewrite of the protocols, although they just announced this week they will not do so. Good call, Dr. Chan.

For a moment, I want to give some props to the Bush Administration. The Obama Administration has admitted it is using the Bush playbook for this swine pandemic, and even President Obama has thanked the former president for his leadership in providing a roadmap to management of this crisis. And yes, it is a crisis. ANY flu pandemic is a crisis-in-the-making. We won't know just how bad of a crisis it is until many days from now.

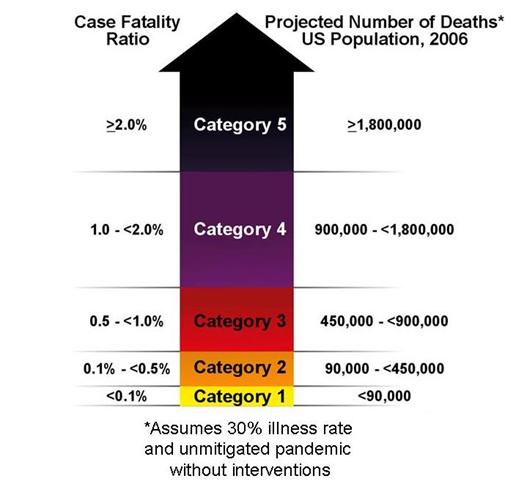

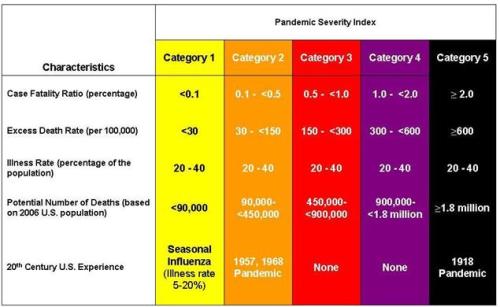

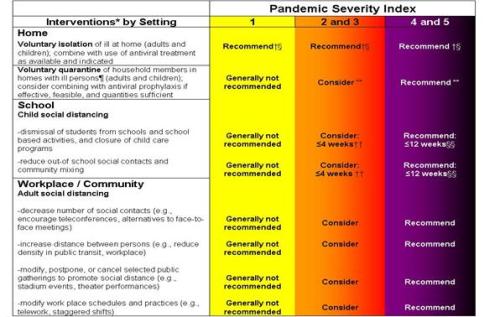

Part of that playbook includes the ingenious move by HHS/DHS to classify pandemics according to a kind of Saffir-Simpson intensity scale. As fans of the Weather Channel and residents of any state within 250 miles of a coastline know, the Saffir-Simpson Scale measures hurricane intensity. What HHS/DHS did was take that metaphor and apply it to pandemics.

HHS/DHS have been using that Saffir-Simpson scale to measure response and move resources since Day One of this crisis. It is so simple and easy to understand, more mainstream media attention should be placed upon it. And I dare say if the other nations of the world had also applied it, or something similar to it, there would not be so much angst and political pressure applied to stifle a Phase Six declaration.

Look at the charts below to understand the United States' approach to this problem.

I frequently refer to this master chart as the "Saffir-Simpson" scale for pandemic lethality. For those nations lobbying to slam the door on the WHO's desire to declare a pandemic, let me ask: has your planning taken the following items into account? See below.

I frequently refer to this master chart as the "Saffir-Simpson" scale for pandemic lethality. For those nations lobbying to slam the door on the WHO's desire to declare a pandemic, let me ask: has your planning taken the following items into account? See below.

The way I read it, we are currently somewhere between Category One and Category Two pandemic status in this country. However, and despite the mainstream media's decision to ignore what is happening all around them, this virus is killing far more Americans now than it did thirty days ago. It is being reported in the surviving hometown daily newspapers in each edition. This means the virus is circulating freely in our communities and continues to attack and, sometimes, kill. It is not going quietly away; it is continuing to spread, which of course is also what we are seeing across the globe. At last count, some 64 nations had the virus, and no nation is declaring itself virus-free. Except maybe North Korea, and that nation has collectively lost its mind anyway.

It is almost worthless at this point to try and track numbers of infections strictly by swabbing throats and noses. We now have to assume, as the New York health officials have assumed, that any case of influenza is now swine flu. Any case of summer flu (which is unheard of in seasonal flu, by the way) should, by definition, be considered the pandemic strain by default.

My Blackberry is going off multiple times a day with reports of confirmed H1N1 swine flu deaths across America. Chicago: A 20-year-old pregnant woman dies after giving birth. Deaths now reported in many states.

People say: No biggie, it's not a killer, so what's the big deal?

In Egypt, recent news reports talk of a village with a confirmed H5N1 human case ( a 4-year-old) and some 39 suspected follow-on infections. A person is testing positive for H5N1 in Egypt at the rate of one every three days. And we don't have any idea of the number of human H5N1 infections in Indonesia; the Health Ministry adopted a policy of only releasing human H5N1 cases every few months. the only inklings of what is occurring in Indonesia come from news accounts, many of which are quickly denied by the government.

As swine H1 takes its victory lap around the planet, it will invariably create local versions of itself. And it will (if it has not done so already) eventually and inevitably be introduced to H5N1 avian flu, either in the respiratory tract of a pig or a human. How those viruses behave together, only God can predict.

So let's go to Phase Six, remind nations of the excellent chart and methodology of HHS/DHS, and begin planning for an unpleasant autumn flu season.

Mystery of Zambian hemorrhagic fever solved -- it's Lujo (and yes, it's new)

A few months ago, I blogged on the appearance of a mysterious new fever that behaved much like Ebola.In that blog, titled (and linked here) called Do we have another species jump in Africa?, I speculated (as did the rest of the world) that we had ourselves another new, species-jumping virus.

DINGDINGDING! Yes, it's new. It's name is the Lujo virus. Yes, as suspected, it is an arenavirus, which is normally carried and spread by rodents.

Now here's the problem: It is an aggressive little sucker, and has an incubation period equivalent to influenza. From my blog of October, 2008:

The index case -- Patient Zero of this new and so-far unknown variant -- is a Zambian who was hospitalized in Johannesburg, South Africa. Two persons who were in the hospital for treatment unassociated with the index patient's disease(nosocomial) also develped symptoms and died. A fourth patient -- a nurse treating the second, NOT the index patient -- is in isolation and is being treated with ribavirin, which helps against lassa fever but is experimental when dealing with this new virus.

Here's a chilling paragraph from the proMED report:

"Arenaviruses cause chronic infection in wild rodents (multimammate mice) with excretion of virus in urine, which can contaminate human food or house dust. Arenaviruses have been found in southern African rodents in the past, but there has been no previous association with human disease. The virus associated with the present outbreak may prove to be a new member of the group." (bold mine)

So we have a new and previously undiagnosed form of arenavirus which has apparently jumped the species barrier from animals (rodents) to humans. Isn't that just lovely? And the virus is highly contagious to boot, as evidenced by the rapid spread to other patients in the hospital -- and the infection of the nurse who was attending one of the follow-on cases.

Now here's the press account, from the AP and found at MSNBC.com:

New killer virus found in Africa

Scientists discover disease that causes Ebola-like bleeding The Associated Press updated 8:17 p.m. ET, Thurs., May 28, 2009

ATLANTA - Scientists have identified a lethal new virus in Africa that causes bleeding like the dreaded Ebola virus.

The so-called "Lujo" virus infected five people in Zambia and South Africa last fall. Four of them died, but a fifth survived, perhaps helped by a medicine recommended by the scientists.

It's not clear how the first person became infected, but the bug comes from a family of viruses found in rodents, said Dr. Ian Lipkin, a Columbia University epidemiologist involved in the discovery.

"This one is really, really aggressive," he said of the virus.

A paper on the virus by Lipkin and his collaborators was published online Thursday on in PLoS Pathogens.

The outbreak started in September, when a female travel agent who lives on the outskirts of Lusaka, Zambia, became ill with a fever-like illness that quickly grew much worse.

She was airlifted to Johannesburg, South Africa, where she died.

A paramedic in Lusaka who treated her also became sick, was transported to Johannesburg and died. The three others infected were health care workers in Johannesburg.

Investigators believe the virus spread from person to person through contact with infected body fluids.

"It's not a kind of virus like the flu that can spread widely," said Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which helped fund the research.

The name given to the virus — "Lujo" — stems from Lusaka and Johannesburg, the cities where it was first identified.

Investigators in Africa thought the illness might be Ebola, because some of the patients had bleeding in the gums and around needle injection sites, said Stuart Nichol, chief of the molecular biology lab in the CDC's Special Pathogens Branch. Other symptoms include include fever, shock, coma and organ failure.

Samples of blood and liver from the victims were sent to the United States, where they were tested at Columbia University in New York and at CDC in Atlanta. Tests determined it belonged to the arenavirus family, and that it is distantly related to Lassa fever, another disease found in Africa.

The drug ribavirin, which is given to Lassa victims, was given to the fifth Lujo virus patient — a Johannesburg nurse. It's not clear if the medicine made a difference or if she just had a milder case of the disease, but she fully recovered, Nichol said.

The research is a startling example of how quickly scientists can now identify new viruses, Fauci said. Using genetic sequencing techniques, the virus was identified in a matter of a few days — a process that used to take weeks or longer.

Along with Fauci's institute, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Google also helped fund the research.

© 2009 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

URL: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/30989694/

The link to the study, published in the journal Public Library of Science Pathogens, is at:

http://www.plospathogens.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.ppat.1000455

But wait, there's more! In my December post, I make reference to a woman who died on a Virgin flight from Johannesburg, South Africa, to London in May of 2006. The initial speculation was that she died of Ebola, but we never had a follow-up news story. I strongly urge health authorities to retest her samples to determine if she died of Lujo. that would give us a glimpse of how old this "new" virus really might be.

Now this virus does not travel as influenza does -- it is not "airborne," as they say. It can currently only be transmitted via contact with bodily fluids. The good news within the bad news is that the virus does seem to be sensitive to the antiviral ribavirin, which is used to treat Lujo's distant viral cousin, Lassa Fever. And it is still a rare virus.

So my question of last October -- Do we have another species jump in Africa? -- is answered. The answer is Yes. And it could be a doozy.

AP news story points us to 1946 H1N1 (maybe) pandemic as immunity guide

Earlier today, I pointed out with some thumping of the ol' chest that the CDC has indirectly confirmed my theory of late April regarding swine flu; namely, that we could compare this event with the 1946-47 pandemic/epidemic of H1N1 and the 1951 H1N1 severe epidemic to see if there was a correlation.

The New York Times article was the first confirmation of that. Now, the AP has also written on the topic. But their story is more precise in the age group (persons ages 60 and above) that seem to have natural antibodies against 2009's swine H1N1.

A simple subtraction of the number 60 from the number 2009 (or 2008 if you prefer, since the virus apparently first manifested itself in September 2008 in Mexico) yields the number 1948. This is so close to the 1946-47 severe epidemic that it cannot be considered coincidence.

As I have mentioned many times previously, the 1946-47 epidemic may have, in fact, been a pandemic of influenza. It was certainly an epidemic, and was by accounts as severe, illness-wise, as the 1957 H2N2 "Asian flu" pandemic, with roughly the same mortality, which was serious but not apocalyptic.

Textbook research shows that flu seasons had been relatively mild from 1930 until 1946, when all viral Hell broke loose. A serious antigenic event -- a huge drift, or perhaps a more likely antigenic shift due to reassortment of human flus -- took place. It rendered vaccines useless (sound familiar?) and started a new chain of H1N1 flu that culminated in yet another antigenic seismic event in 1951. That virus caused more epidemics until it was deposed by H2N2 in 1957.

It is highly unlikely that antibodies to pre-1946 influenza are helping seniors today. In my own opinion, it must have been the 1946-47 strain of H1N1. And that would seem to indicate a swine background for that mutation, but I will leave that for the researchers.

At any rate, the roadmap is opened up and flattened out for viral researchers. Good luck to them.

Heeding Dr. Sandman's advice on swine H1N1 risk communications

I just read a Tweet from my buddy Mike Coston, aka FLA_MEDIC, blogger of great repute at Avian Flu Diary. He mentioned an article in Nature by Dr. Peter Sandman, one of the world's leading risk communication experts. I encourage you to follow the link and read it now. I'll wait.

I just read a Tweet from my buddy Mike Coston, aka FLA_MEDIC, blogger of great repute at Avian Flu Diary. He mentioned an article in Nature by Dr. Peter Sandman, one of the world's leading risk communication experts. I encourage you to follow the link and read it now. I'll wait.

OK, welcome back. Didn't that all sound familiar? Having deja vu? that is because it sounds similar to my blog of April 28th, titled Mixed messages, cafeteria-style preparedness won't cut it in swine flu fight. In that blog, I cover many of the same themes. But Dr. Sandman puts things much more succinctly and with much greater gravitas than I ever could.

I met Dr. Sandman in February 2007 in orlando at the CIDRAP pandemic conference. The man and his work are both highly valued and woefully underutilized, I am afraid.

The thing I most remember about then-HHS Secretary Mike Leavitt, a former governor of Utah, is his suggestion -- painfully repeated over and over and over again -- that the easiest way to stock up for a pandemic was "When you go to the store to buy tuna, for every three cans you buy, get a fourth and put it under the bed." Overall, the entire Bush Administration message on pandemic preparedness was (uncharacteristically) clear, sensible, and sage. It was borne of Bush's own reading of John Barry's seminal work The Great Influenza," THE history of the 1918 pandemic.

President Obama's administration seems to have completely disregarded the role that concise risk communication must play in effective management of a flu pandemic. The role of individual responsibility needs to be played up, not downplayed in favor of "nothing to see here, move along." the American people can take it: Tell them exactly what they need to hear. Especially the part they never want you to hear: government can do very little to ensure your personal safety or health during a flu pandemic. That itself may be anathema to their way of thinking, but the truth is the truth.

Richard Besser, the acting director of the CDC, isn't understating the risk. He says he is "very concerned", but expresses his concern with a soothing bedside manner. He doesn't have that rumpled, exhausted emergency-manager look that the Nuclear Regulatory Commission's Harold Denton perfected in the 1979 Three Mile Island crisis. Denton left people feeling that the risk was serious and that they were in good hands. Besser says it is serious but leaves us feeling that he doesn't want us to worry much.

Still, I don't fault Besser for looking and sounding reassuring. Good crisis communication means saying alarming things in a calm tone, and he is doing exactly that.

The problem is that he isn't giving us anything to do except being hygienic. He keeps telling us, accurately, that the CDC is being aggressive in its response to the outbreak. But he is not asking the public to take further action. He needs to urge citizens, schools, hospitals and local governments to follow Leavitt's advice.

Instead, we have a surreal situation in which the federal government has released one-quarter of the Strategic National Stockpile of antiviral drugs, so there will be enough oseltamivir (Tamiflu) to deploy to millions of sick Americans. But it hasn't yet asked those Americans to stock up on tinned fruit and peanut butter.

It's time to talk peanut butter, tuna and bottled water. But not for swine H1; for any calamity. As I said in my late April blog:

So what should we be telling people? We should be telling them to prepare and to learn more about influenza. I am not talking about the Romero-esque TV commercials that the Ford Administration ordered up during the 1976 swine flu scare. I am talking about telling people to get their "hurricane kits" or "earthquake kits" restocked and brought up to speed. It is time to re-educate the American people on previous pandemics and previous near-misses, such as 1946 and 1951, with viruses that were also H1N1 but were much more virulent and, some thing, either swine-like or were actual swine influenzas that jumped the species barrier back in the day.

Telling people to buy one to two weeks' worth of food, water and medicines to prepare for hurricane season -- an annual hit-or-miss proposition with a clear historical precedent of occurrences -- is not considered folly; it is considered prudent.

Great minds think alike. Thank you for a great article, Dr. Sandman.

New York Times' McNeil: Older Americans may be immune to Swine H1N1 flu

Well, well, well. It is always nice and gratifying to have a theory confirmed by the mainstream media and the flu experts.

Let me explain: A few weeks ago (April 26th), I blogged that our current swine H1 might be a relative of the same virus that appeared in 1946-47 and 1951. I also proferred that theory to one of the world's top influenza experts via email. Trust me on that: It is literally a matter of public record.

Now comes an article written by the New York Times' Donald McNeil Jr., who is to the U.S. what Helen Branswell is to Canada when it comes to infectious disease newspaper journalism. In it, Mr. McNeil quotes Dr. Daniel Jernigan of the CDC, who states very clearly that informed opinion is coalescing around a theory that pre-1957 H1 successfully conferred immunity to now-older Americans.

The Times article is somewhat incomplete. It insinuates that all H1 was pretty much the same following 1918, just getting more and more diluted. If you look at influenza textbooks of the past twenty years or so, however, what actually happened is that an event of great significance produced much more severe epidemics of H1N1 in 1946-47 and 1951. It has been postulated that swine H1 might have crossed the species barrier in those epidemics, or a random mutation/mutations changed the gene segments just enough to cause some above-average morbidity.

Among influenza circles, debate still rages (that is a relative term, as "rages" for them might be a "harrumph" or a discreet rolling of the eyes) about whether or not 1946-47's epidemic was in actuality a real pandemic. There are considerable arguments on both sides, and I have seen the words "1946-47 pandemic" in print on more than one occasion, in more than one text. What is known is that some seminal event occurred that rendfered the seasonal vaccine for that year completely useless. The link atthe previous sentencewill take you to a study conducted by the living influenza legend Dr. Edwin Kilbourne on that very vaccine failure.

While quite possibly a pandemic, the 1946-47 epidemic produced huge spikes in morbidity, or illness. What it did not do, however, is kill a lot more people statistically. That was reserved for the 1951 epidemic of so-called "Liverpool flu."

The 1951 Liverpool flu epidemic was a terrible killer of people, strangely enough, in the English-speaking world. In the scientific paper 1951 Influenza Epidemic, England and Wales, Canada, and the United States, researcher Ceclie Viboud and others describe the impact that strain of H1 placed on Britain and North America. In some sections of Britain and the US Northeast, the case fatailty rate for 1951's H1 was worse than 1918-19!

We are used to uttering two words when discussing influenza antigenic mutations: Drift and shift. Drift is what happens when a virus makes copies of itself (badly). Shift is what happens when a major reshuffling of influenza genes takes place. Shift is what makes pandemics, or so we have always thought. Antigenic shift occurs when reassortment takes place between dissimilar flu strains. For previous descriptions of drift and shift, reassortment and recombination, just search this blogsite and Google the terms as well.

But what if antigenic shift occurs within the H1N1 subtype itself? Is the resultant virus truly a pandemic candidate? Is this what occurred in 1946-47? Is this what occurred in 1951? Scientists think so. From Science Daily of March 7, 2008:

ScienceDaily (Mar. 7, 2008) — The exchange of genetic material between two closely related strains of the influenza A virus may have caused the 1947 and 1951 human flu epidemics, according to biologists. The findings could help explain why some strains cause major pandemics and others lead to seasonal epidemics.

Until now, it was believed that while reassortment -- when human influenza viruses swap genes with influenza viruses that infect birds -- causes severe pandemics, such as the 'Spanish' flu of 1918, the 'Asian' flu of 1957, and the 'Hong Kong' flu of 1968, while viral mutation leads to regular influenza epidemics. But it has been a mystery why there are sometimes very severe epidemics -- like the ones in 1947 and 1951 -- that look and act like pandemics, even though no human-bird viral reassortment event occurred.

"There was a total vaccine failure in 1947. Researchers initially thought there was a problem in manufacturing the vaccine, but they later realized that the virus had undergone a tremendous evolutionary change," said Martha Nelson, lead author and a graduate student in Penn State's Department of Biology. "We now think that the 1947 virus did not just mutate a lot, but that this unusual virus was made through a reassortment event involving two human viruses.

"So we have found that the bipolar way of looking at influenza evolution is incorrect, and that reassortment can be an important driver of epidemic influenza as well as pandemic influenza," said Nelson, whose team's findings appear in the current issue of PLoS Pathogens. "We have discovered that you can also have reassortment between viruses that are much more similar, that human viruses can reassort with each other and not just with bird viruses. " (bold mine)

Nelson and her colleagues analyzed the evolutionary patterns in the H1N1 strain of the influenza A viruses by looking at 71 whole-genome sequences sampled between 1918 and 2006 and representing 17 different countries on five continents.

Big differences in the shapes of these eight trees signified that reassortment events had occurred.

The swapping of genes between two closely related strains of the influenza A virus through reassortment may also have caused the 1951 epidemic, which looked and acted in many ways like a pandemic as well. Deaths in the United Kingdom and Canada from this epidemic exceeded those from the 1957 and 1968 pandemics.

Currently, there are many types of influenza virus that circulate only in birds, which are natural viral reservoirs. Though the viruses do not seem to cause severe disease symptoms in birds, so far three of these viral types have infected humans -- H1N1, H2N2, and H3N2.

Understanding how each strain evolves over time is crucial. H3N2 is the dominant strain and evolves much more rapidly than H1N1. So the H1N1 component of each year's flu vaccine has to be updated less often. In comparison, the H3N2 component of the vaccine has been changed four times over the past seven years.

The H1N1 virus is particularly unusual because it disappeared completely in 1957, only to mysteriously re-emerge in humans in 1977 in exactly the same form in which it had left. It is still not certain what happened to the virus during its disappearance. But since it did not evolve at all over these twenty years, "the only plausible explanation is that it was some kind of a lab escape," says Nelson, who is also affiliated with Penn State's Center for Infectious Disease Dynamics (CIDD). (bold mine)

The Penn State researcher says the study shows that the evolution of a virus is not limited to the mutation of single lineage, and that there are multiple strains co-circulating and exchanging genetic material. The H1N1 and H3N2 strains, for instance, are occasionally generating hybrid H1N2 viruses.

"If we really want effective vaccines each year, our surveillance has to be much broader than simply looking at one lineage and its evolution, and trying to figure out how it is going to evolve by mutation," said Nelson. "You have to look at a much bigger picture."

OK. So here's what this says:

We got so wrapped around the axle of looking for Bird Flu under every duck's behind, and we got so lax at a) swabbing suspected flu patients and b) sending "untyped A" samples to the CDC/WHO, that we completely got snookered (a Southern technical term) by swine H1N1. It seems reassortment between similar subtypes happens all the time (I have seen several reports confirming that H1N2 combination) that this new hybrid swine/avian/human H1N1 could very well be following a path already traveled by the H1N1 viruses of 1946-47 and 1951.

Now let me go a bit further: The Science Daily article also says that H1N1 does not change its genetic makeup easily, nor suffer fools gladly. But its resilience cannot be underestimated. Whether it takes its place in the pantheon of pandemic viruses is yet to be known. And indeed if there is immunity to this virus from baby boomers and older prople, we are having the same argument about "pandemic or not to be a pandemic" that people had in 1947 and 1951 -- arguments still underway today. This also explains why the WHO may be very unwilling to declare a Phase 6 pandemic when this may not actually be a pandemic. Recall that a pandemic by definition includes, at its core, a virus with little to no immunity in the general population.

If billions of people are over age 52, then the criteria for a pandemic virus has not been met -- yet. I say "yet" because I want to also talk about another statistic. And that is that it only took a few years from the 1951 epidemic to the total disappearance of H1N1 in 1957. Recall that influenza plays King of the Mountain. The year 1951 began H1N1's Farewell Tour, although now in retrospect it was one of those Cher/Streisand faux farewell tours, meaning "Farewell until the next big tour's big fat paycheck."

If billions of people are over age 52, then the criteria for a pandemic virus has not been met -- yet. I say "yet" because I want to also talk about another statistic. And that is that it only took a few years from the 1951 epidemic to the total disappearance of H1N1 in 1957. Recall that influenza plays King of the Mountain. The year 1951 began H1N1's Farewell Tour, although now in retrospect it was one of those Cher/Streisand faux farewell tours, meaning "Farewell until the next big tour's big fat paycheck."

So which influenza strain will knock H1N1 back off the mountain? Will it be H5N1? A return of H2N2? You know, there is a developing consensus that pandemic viruses recycle themselves every three to four generations. When there are no more immune people to get in the way of a massive infection wave ( categorized as a lack of "herd immunity"), then an older virus energizes itself and springs forward.

Nobody knows what will happen with swine H1N1. But once again, if history is to tell us anything, it is that influenza is wildly unpredictable and we need to be prepared for anything. And we need to look closely at 1951 and 1946-47 for more immediate answers. Fortunately, many of those who researched those epidemics/pandemics are still with us. Let's use their talents and mine their recollections and get busy.