Entries in influenza and infectious diseases (390)

A Sulfur Cockatoo, a crocodile, a wild boar, and a kangaroo mouse walk into a bar....

One bright spot in a sea of failed national attempts at H5N1 prevention has been the Republic of the Philippines. Besides the 2005 Meningococcal septicemia/bird flu scare and a 2005 small low-path H5N1 outbreak, the island nation has worked itself to be (so far) bird flu-free.

So I have probably just jinxed them! Anyway, their vigilance has paid off again, as the following news story attests:

Government agents in Davao City arrested Sunday an Indonesian and two Filipinos Sunday for smuggling into the country exotic birds from Indonesia, a bird flu "hotspot" in Southeast Asia.

Government agents in Davao City arrested Sunday an Indonesian and two Filipinos Sunday for smuggling into the country exotic birds from Indonesia, a bird flu "hotspot" in Southeast Asia.Sun.Star Davao reported Tuesday that the confiscated animals were exterminated Monday to prevent the possible spread of avian influenza.

The National Bureau of Investigation (NBI), whose agents made the arrest and seizure, said the extermination was done in its regional office in Davao City.

There are already 101 confirmed cases of bird flu in humans in Indonesia, 80 of which have been fatal.

The Philippines, meanwhile, has so far maintained its bird flu-free status in the region.

Confiscated from the suspects were a Bird of Paradise, three Rainbow Lories, a Black Palm, a Sulfur Cockatoo, two Gaski Lories, a Black Cut Lory, a Black Lory, a crocodile, a wild boar, and a kangaroo mouse.

The NBI identified the suspected smugglers as Indonesian national Randy Mandumi Makaginggi; Mike Antucilla, 36, a resident of Davao City; and Renante Toledo a.k.a. Nante, a resident of Lasang, Davao City. They were arrested at noon Sunday.

Antucilla, the primary suspect, travels to Indonesia at least once a month to get stocks and was using the Indonesian national as interpreter and as his accomplice.

Antucilla and Toledo are now detained at the NBI and face charges for violating the Wildlife Conservation and Protection Act. Makaginggi was brought to the Bureau of Immigration to face appropriate charges.

"This is a month-long surveillance and product din of intelligence reports from the agents of the bureau," said Exzel Hernandez of the NBI.

Hernandez said the suspects were said to be smuggling various contraband like firearms, ammunition, shabu while using the birds as cover for the smuggled items.

He said the suspects would also smuggle in snakes on a "per order" basis.

The NBI said it is verifying reports that the same gang was also involved in human smuggling.

Hernandez said the birds and other creatures were turned over to Department of Agriculture (DA) instead of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) Protected Areas and Wildlife Bureau (PAWB).

Under the setup of the National Avian Flu Task Force, the DA's Bureau of Animal Industry is the lead agency for bird flu for as long as there is still no human infection reported.

Only two weeks ago, another case of bird flu infection on a three-year-old girl was confirmed in Indonesia. She has since recovered.

Outbreaks of the virus both in animals and humans continue to be confirmed in Indonesia, the latest of which was just last month. - GMANews.TV

Virginia's sick turkeys, blowflies, and an Indonesian mystery

Well, the discovery that low-path H5N1 was present in a flock of some 54,000 turkeys in Virginia didn't seem to phase anyone. I should explain that low-path H5N1 is found in wild birds across the United States all the time. In fact, Delaware seems to be routinely testing and finding low-path H5N1 in wild birds (and maybe the WHO and OIE and FAO and the whole "alphabet soup gang" should simply outsource wild bird testing to Delaware?).

Well, the discovery that low-path H5N1 was present in a flock of some 54,000 turkeys in Virginia didn't seem to phase anyone. I should explain that low-path H5N1 is found in wild birds across the United States all the time. In fact, Delaware seems to be routinely testing and finding low-path H5N1 in wild birds (and maybe the WHO and OIE and FAO and the whole "alphabet soup gang" should simply outsource wild bird testing to Delaware?).

But finding LP H5N1 in wild birds and finding it in a Virginia turkey farm are two different things. And, as I have said over and over again -- if left untreated, low path bird flu goes in, and high path bird flu comes out. This reality has presented itself countless times in poultry farms across the nation and, indeed, across the world.

Recall that up until 2003, the world leader in avian influenza outbreaks among domestic poultry was -- drum roll, please -- the United States of America. As written in Dr. Michael Greger's excellent tome "Bird Flu: A Virus of Our Own Hatching," Greger presents a compelling argument that it might be the Delmarva Peninsula within the Delaware, Virginia and Maryland triangle, and not Guangdong, China or Jakarta, Indonesia, where a pandemic launches.

So you gotta love the comments from the United States Department of Agriculture's Dr. John Clifford, from USDA's National Veterinary Services Laboratories (from Reuters).

The turkeys had antibodies to a low pathogenic form of the H5N1 avian influenza virus, Clifford said. This strain of H5N1 does not usually make birds ill, although it could potentially change into a more dangerous form if allowed to spread.

"Every indication is that the virus detected is consistent with the North American strain of low pathogenic H5N1, which is not a human health concern," Clifford said in a statement.

"The turkeys showed no signs of illness, and there was no mortality. Thus far, there is no evidence the virus is actually present in the samples collected. The testing detected only antibodies, which indicate possible past exposure to the virus."

Allow me to translate this obviously encoded message. What he means is not "possible,' but "likely" exposure to the H5N1 virus, even if low-path. Turkeys do not get hatched with H5N1 in their veins. This means that a flock of 54,000 turkeys -- destined for the dinner tables of America and elsewhere -- had exposure to H5N1 enough to have produced antibodies. This means that very, very recently (remember, turkeys do not live very long, unless pardoned by the President at Thanksgiving), there was H5N1 on that farm. And the turkeys were exposed to it. According to statistics provided by animalaid.org, turkeys are slaughtered at 12 to 26 weeks, even though they may live to ten years of age. However, according to Website maguirefarm.com, turkeys bred for food usually cannot support their weight after a year. So, this means that sometime in the past 12 weeks to a year, low-path H5N1 was present in significant volume on the farm in question. And it got past the breeders and the State and Federal authorities. So it is possible that a low-pathogenic H5N1 could have entered this unnamed Virginia farm, circulated among the 54,000 birds, and its progeny could have been high-path H5N1. Now that is a sobering thought, that surveillance in the US missed this important development.

West Virginia, hit with its own heavily publicized low-path H5N2 outbreak just weeks ago, cancelled a poultry festival and is taking other steps to ensure the virus does not cross its border with Virginia. From an AP story in the Charleston Daily News:

Although the virus has not been found in West Virginia, the state Poultry Association decided Monday to cancel the five-day festival because area poultry farmers attending the festival might unwittingly transport the virus to other farmers, said Emily Funk, the association's executive secretary.

"When we have an avian outbreak like this we try not to get together," she said. "Try not to go to the grocery store. We try not to associate with each other."

"The festival is held in Moorefield, which will go ahead with its carnival and golf tournament for nonfarming residents. What will be missing are the beauty pageant and various education dinners and activities sponsored by the association, she said.

It's at least the second time since the 1980s that the festival has been canceled, she said.

State Agriculture Commissioner Gus Douglass said the low pathogenicity avian influenza found in a turkey flock in Mt. Jackson, Va., about 71 miles southeast of Moorefield, is not the same as the bird flu found in Southeast Asia, Europe and other countries.

Folks, the farmers do not associate with each other because they can shed virus from their clothing and shoes/boots, to be picked up by their neighbors -- and because they can also hypothetically be asymptomatic carriers of low-path H5N1.

In another story, North Carolina State University reports that H5N1 can remain active in the stomachs of common houseflies for up to three hours. This study cited a 1985 study of housefly infestations with avian influenza stemming from 1983's huge H5N2 outbreak in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. That study showed that more than a third of the houseflies trapped during the H5N2 outbreak had bird flu virus in their guts. Following a Kyoto, Japan outbreak of "bad" H5N1 in 2004, more evidence was collected to support the flies-as-vectors theory.

In another story, North Carolina State University reports that H5N1 can remain active in the stomachs of common houseflies for up to three hours. This study cited a 1985 study of housefly infestations with avian influenza stemming from 1983's huge H5N2 outbreak in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. That study showed that more than a third of the houseflies trapped during the H5N2 outbreak had bird flu virus in their guts. Following a Kyoto, Japan outbreak of "bad" H5N1 in 2004, more evidence was collected to support the flies-as-vectors theory.

Nonetheless, nothing of consequence has been done to reduce or eliminate houseflies as a serious vector of avian influenza within the poultry industry.

Let me say that I know the masked R&B artist Blowfly personally and he is not responsible.

Now, a quick look at the story coming out of Indonesia that a six year old boy who died of H5N1 was not exposed to poultry. That the story was broken by the Indonesian Agricultural Ministry is amazing. Here is an official organ of the Indonesian government admitting that this young lad had no exposure to poultry or wild birds -- but he did, apparently, go to the zoo recently. From a recent Reuters story:

Now, a quick look at the story coming out of Indonesia that a six year old boy who died of H5N1 was not exposed to poultry. That the story was broken by the Indonesian Agricultural Ministry is amazing. Here is an official organ of the Indonesian government admitting that this young lad had no exposure to poultry or wild birds -- but he did, apparently, go to the zoo recently. From a recent Reuters story:

It is always a concern when the cause of a human infection cannot be traced as it makes infection control more difficult.

Runizar Ruesin, the head of the health ministry's bird flu centre, said that at least 20 of chickens near the boy's school had died suddenly.

"But we are still investigating whether he had a contact with sick or dead chickens in the neighbourhood," the official said.

A spokeswoman at the Jakarta hospital where the boy was treated said that along with some chickens dying near the boy's school there were also water fowl in the school area.

"There are a lot of water fowl roaming near the boy's school although they probably didn't get into the school," said Tuty Hendrarwardati, a spokeswoman for the Sulianti Saroso hospital.

The boy, who had been suffering from fever before visiting relatives in the city of Bandung on June 25, had also been to the zoo, she said.

Even if the boy was infected by a neighborhood chicken, look at the ease with which the infection took place. The Elephant in the Room is the question of the samples the Indonesian government finally gave up to the WHO, following their little spat over vaccine rights and first dibs. What precious time was lost in isolating changes in the virus? And what are those changes? They are apparently enough to cause the Indonesian government to begin rush production of a prepandemic vaccine while ignoring WHO entreaties to stockpile rather than inject. The Indonesian government has decided to "stockpile vaccine in people, not buildings," which was the rallying cry of the Ford Administration's Swine Flu decision in 1976. And the Indonesian government has one heckuva lot more evidence to support its decision than Ford did in 76. Dr. Harvey Fineberg, onetime head of Harvard's public health school and now president of the Institute of Medicine, wrote of this decision in his book Decision-Making on a Slippery Disease. Dr. Fineberg and I correspond frequently on pandemic public policy issues, and his book should be required reading for anyone interested in the public policy angle of a looming pandemic. The Ford Administration's decision to stockpile in people was assailed for not having enough surveillance or actionable intelligence on the virus to warrant exposure to the vaccine's side effects. And even though hundreds of people wound up testing H1N1-positive, only one soldier died.

In contrast, Indonesia has the highest H5N1 death rate in the world, with the virus so endemic that a six-year-old boy can die from it by apparently just walking by sick chickens, seeing waterfowl or attending a local zoo. Or from some other vector, be it blowfly, cat, or bird. Surveillance shows that the world may have dodged the Indonesian pandemic bullet twice in the past fourteen months alone by quick action from the Indonesian government, the United States and the WHO. Maybe we should pay much closer attention to what is really going on down there.

Is Kelbra Lake the new Qinghai?

Reports coming out of Germany continue to parlay bad news after bad news. It appears that a small lake in central Germany may be the most significant body of water to enter the lexicon of H5N1 trackers since China's Qinghai Lake in May, 2005.

Reports coming out of Germany continue to parlay bad news after bad news. It appears that a small lake in central Germany may be the most significant body of water to enter the lexicon of H5N1 trackers since China's Qinghai Lake in May, 2005.

That Chinese body of water spawned the most significant spread of high-path H5N1, now known as Clade 2.2, or the Qinghai strain of H5N1. This subtype has spread across Asia, Europe and now Africa. It reaches from the Ivory Coast to the Middle East, to France and Britain, to Moscow and Siberia.

Now, Qinghai H5N1 has gained a solid footing in a small (about 3 square miles) lake called Kelbra in central Germany. Formed as the result of a dam, this arfificial lake is close to a popular tourist campground. And it appears to be teeming with H5N1. More than 300 dead birds have been fished from the water and tested in the past few weeks, and the overwhelming majority are H5N1-positive.

If this is not bad enough news, now small farms in adjacent nation-state Czech Republic are experiencing problems with H5N1 in their flocks, and thousands of birds were and are being culled across Europe. France has found H5N1 in swans, and France and Germany have raised their threat levels accordingly. Egypt, of all nations, has now blocked the import of French and German poultry. And with each passing day, the body count of dead wild birds increases across the continent.

H5N1's renewed spread across Western Europe reveals it once again to be a robust, hearty and evolving pathogen. Its ability to "go underground" and smoulder, then reappear at the most unlikely times, continues to confound the world's leading experts on influenza.

Why anyone on this planet would think that H5N1 is a non-threat does not understand influenza. And that is because the people on this planet who do understand influenza have been warning us for years that this disease is incredibly crafty and resilient.

This also underscores a growing and neglected problem; namely, the lack of a reliable test on live wild birds for H5N1. The story is the same across the globe: Live wild birds test negative for H5N1, wild birds die, wild birds test positive for H5N1. Is this because we do not have sufficient numbers of birds tested? Is this because we do not have a reliable test for the presence of H5N1 in live wild birds? Are we using the wrong test on the wrong birds? Are we swabbing the "wrong end" of the birds? Are we not swabbing throats and only focusing on the cloacal (rear end) area?

Anyone who has seen the lengths researchers have to go to just to capture wild birds for testing understands the extreme difficulty in the process. Nets, snares, traps, etc. are a pain in the cloaca. No wonder the numbers tested are so low!

But test we must, because we must know if Kelbra has become the Qinghai of Europe: The new endemic source of H5N1 for an entire continent.

Plans suck. Planning rocks!

Or, Ike for the YouTube generation.

Patrick Thibodeau works quickly! The Computerworld senior editor was just on the phone with me last night, asking me about Gartner analyst Ken McGee's exasperation at IT's lack of pandemic planning. I feel his pain. Here's the link to the Computerworld article:

What was left out of his excellent article was my YouTube version of Ike's planning adage. Dwight D. Eisenhower said, "The plan is useless; it's the planning that's important." Or, as the YouTubers would say, "Plans suck. Planning rocks!"

What was left out of his excellent article was my YouTube version of Ike's planning adage. Dwight D. Eisenhower said, "The plan is useless; it's the planning that's important." Or, as the YouTubers would say, "Plans suck. Planning rocks!"

For a guy who had to plan the whole enchilada called World War II in Europe, or more accurately oversee all the planning, we should heed his advice. Here was a guy, the project manager for the biggest undertaking in world history, and he certainly had his share of ups and downs (anyone who has read Rick Atkinson's superb history of the American Army in North Africa, An Army at Dawn, can see how Ike grew both as a planner and as a leader of men and women). Ike's point is that plans will fail, but a mature planning process will help you prevail. An excellent link is this one: http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m3257/is_11_59/ai_n15863428 .

A major State agency recently decided to hire an expensive consultant to write its disaster recovery and COOP (Continuity of Operations) plans. What a mistake! Where will this rich and influential consultant be when the winds blow, or the people fall ill, or the building catches fire? Somewhere in Cancun, probably. Hiring consultants to write your DR/COOP plans is like hiring mercenaries to fight your end of a civil war. Where's the skin in the game? What lessons are learned by your staff? None and none.

Your people are your greatest asset. Leverage them to write your plan. Think business processes. Think how you can innovate your organization's way around those potential showstoppers. Remain flexible. But for God's sake, don't outsource your planning process! Else you will fail. Certainly use consultants to facilitate the planning process; the meetings; and perhaps use them to scribe the entire process. But if you use consultants to come in, interview everyone and then write a plan all wrapped up in a pretty little silk bow, you are doomed. For when that plan begins to unravel (as all plans do to some extent, in wartime and in times of great stress and confusion), then you are absolutely toast. And so is your organization.

You have heard of the "Fog of War," the cloud of uncertainty and doubt that takes place in every battle, when even the most meticulously laid plans begin to wither in the face of uncertainty and stress. That is precisely what Ike is speaking of. A mature, robust planning process with veteran decision-makers thinking on their feet -- now THAT is what the process is all about!

I recall a scene in Clint Eastwood's classic film Heartbreak Ridge, when Everett McGill's character orders Eastwood's Gunny Highway to set up an ambush at a specific location. Sergeant Choozoo, an observer, remarks sardonically, "It's always good to know where and when you'll be hit."

The consultants aren't THAT smart! Nobody is.

Top ten reasons why we haven't had an influenza pandemic (but will one day, probably soon).

With apologies to David Letterman, here is a quick list that you can keep handy and use to win arguments on the likelihood of an influenza pandemic. Feel free to add to this list, but it is written to be easily and quickly understood.

Top 10 reasons why we have not seen a pandemic since 1968:

10. The H5N1 virus has not “made it” around the globe – at least we have not seen high-path H5N1 yet in North America (at least none that any authority is willing to admit).

9. Surveillance of poultry and wildfowl, including aquatic wildfowl, has improved exponentially since 1968.

8. Rapid typing of influenza genetics allows public health officials to quickly make good decisions and move decisively to contain virus.

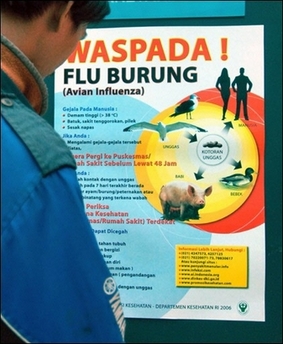

7. Education campaigns help to better promote awareness, especially in nations where H5N1 is becoming endemic. So when people get sick, or poultry gets sick, people are now a little more likely to report it.

6. Mass culling of poultry has beaten back the virus many, many times around the world. One major influenza researcher even went so far as to state that a pandemic strain of H5N1 has probably already died with a mass cull somewhere in this world.

5. Financial compensation for culled poultry helps convince some farmers to report deaths of poultry to the authorities.

4. The neuraminidase inhibitor antivirals (Tamiflu in particular) have been repeatedly effective in reducing H5N1 symptoms and ultimately in saving patients, but only in cases where a) the virus may not be as lethal, and b) when administered within 24 – 48 hours after onset of symptoms.

3. The WHO and global health authorities are ready to fly in supplies and “stamp out” outbreaks quickly. The August, 2006 “Tamiflu blanket” of 2,000 Indonesian villagers in four separate hamlets serves as evidence of the ability of public health authorities to combine Reasons #9, #8 and #5 into a coordinated action plan.

2. The Hong Kong government’s 1997 action to cull every bird in the city as the first suspected human-to-human transmission of the “new” H5N1 virus probably saved the world from a pandemic. Saved, or at least delayed the pandemic.

1. Global seasonal flu vaccine programs -- and the WHO's trying to pick the "Super Bowl winner" of three viruses (two Influenza A's and one B for the trivalent formula) in the February before the upcoming flu season -- have proven pretty accurate. They miss the B formulation more often than they miss the A, but still it has helped reduce the amount of seasonal flu, which helps reduce the potential for a pandemic. After all, each of us is a potential "mixing vessel" for a reassortant pandemic strain..

co-#1: We are damned lucky.

Top 10 Reasons why, despite all these efforts, we will still have a pandemic one day and probably soon.

10. H5N1 is becoming endemic in many parts of the planet, especially where people live in close physical proximity to poultry. It is a mutating fool and cleverly defies attempts to kill it. It is a supremely adept player at "King of the Mountain," which is the game all influenza viruses play.

9. Financial compensation for culled poultry helps somewhat, but the amounts paid usually are far short of actual losses incurred. If farmers do not feel that reporting avian flu losses are worth it in financial terms, they may (and already do) decide not to report the infections – unless their own family members become infected.

8. Smuggling of poultry, exotic birds and fighting cocks continues to accelerate. While not likely to be a principal source of spread of the disease, smuggling can nonetheless cause new outbreaks (ask the Vietnamese about their own “Ho Chi Minh Trail” issues along their border with China).

7. Modern industrial farming practices may actually and inadvertently encourage the spread of virus. Even a tiny particle of virus, trampled underfoot and brought into a poultry shed by a worker or farm machine, can kill thousands of poultry. And if left unchecked, even a “low path” avian flu can incubate, recombine with itself and emerge as a lethal, highly pathogenic influenza virus.

6. Despite the best 21st Century medicine and technology, avian flu of all types continues to spread and the frequency continues to accelerate. Witness the recent outbreaks of H7N2 in the Delmarva (Delaware, Virginia and Maryland) peninsula of the United States (2004), the H5N2 outbreak in West Virginia (2007), the outbreak of H7N7 in the Netherlands and other parts of Europe which killed a veterinarian and infected at least 89 people via human-to-human transmission and possibly hundreds more (2003), and the outbreak of H7N2 in Wales which also infected 17 humans (2007).

5. Globalization has also inadvertently encouraged the spread of virus. Witness the Bernard Matthews disaster of early 2007. Hungarian-raised poultry, shipped to England for processing, carried high-path H5N1 with it. This was introduced into one shed, and then workers carried the virus to three adjacent sheds. In the end, over 160,000 turkeys had to be killed and disposed of. The Hungarian poultry were contaminated, in all likelihood, by wildfowl droppings laden with H5N1 virus that were carried into turkey sheds.

4. Migratory wildfowl continue to transport the H5N1 virus, along with every other flu virus known to Humankind, in their bellies. Migratory wildfowl are the custodians and reservoir of avian influenza. As they shed virus, it either dies or is picked up by other creatures.

3. H5N1 has jumped the species barrier. In Indonesia, a study postulated that up to 20% of all stray cats in the archipelago nation showed antibodies to high-path H5N1. That means cats can be asymptomatic carriers of the most potentially lethal virus ever seen. The Indonesian television videos of Army regulars accompanying healthcare workers into residential neighborhoods to swab the mouths of housecats is chilling.

2. The only continents where H5N1 does not have a strong foothold are the Americas, Australia and Antarctica. H5N1 can be found from sub-Saharan Africa to the Middle East, most of Europe, Asia, and Indonesia. Only in Europe has human death not yet occurred from H5N1. Unfortunately, that statistic can be wiped out with a single transcontinental or transoceanic airplane flight.

1. History is against us. In the past 300 years, no fewer than ten influenza pandemics have ravaged the world. Some, such as 1918’s Spanish Flu and the pandemic from 1562–1568 were extremely lethal. The 1562 pandemic may have had a death rate higher than 1918’s, which is almost unthinkable. Others, such as 1889’s, had a less lethal but still severe effect on the planet.